| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 3, June 2020, pages 95-98

Unilateral Cardioembolic Stroke in a Patient With Aortic Arch Anomaly

Ana Hossein Zadeh Malekia, Reza Bavarsad Shahripoura, Andrew Wilnera, b

aDepartment of Neurology, University of Tennessee Health Science center, Memphis, TN, USA

bCorresponding Author: Andrew Wilner, Department of Neurology, University of Tennessee Health Science center, Suite 415, 855 Monroe Avenue, Memphis, TN 38163, USA

Manuscript submitted March 18, 2020, accepted March 31, 2020, published online May 30, 2020

Short title: Cardioembolic Stroke in Aortic Arch Anomaly

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr584

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive 29-year-old man presented with pre-syncope and acute left hemispheric infarction in multiple vascular territories. Thorax computed tomography (CT) with contrast showed bovine aortic arch and a left atrium large mass. On transthoracic echo, a 2.1 × 2.6 cm mass pointed to the heart as the embolic source. Successful surgical resection revealed cardiac myxoma. Although this presentation mimicked artery to artery embolization but having a bovine aortic arch can contribute to this stroke propensity to the left hemisphere.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular disease; Stroke; Embolism; Cardiac

| Introduction | ▴Top |

In the population below the age of 45 years old, the mechanism of stroke is cardioembolic in 15-35% and cryptogenic in 35% of cases [1].

Clinically, physicians suspect cardioembolic infarctions when strokes are bi-hemispheric and in multiple vascular territories. However, anomalies in the configuration of the proximal arterial tree may result in unusual presentations [2]. Consequently, the anatomy of the aortic arch and its branches should not be overlooked when investigating stroke etiology.

There are almost 20 variants of the aortic arch [3-7]. The bovine syndrome, manifested by our patient, is one of the most common anatomical variations with a prevalence of 13% [3]. This unique configuration can result in the predilection of embolic materials to the left hemisphere [2] and may mimic artery to artery embolic stroke syndromes, which tend to be unilateral.

In this manuscript, we report an embolic stroke that included multiple vascular territories restricted to the left hemisphere in a patient with a bovine aortic arch anatomical variation (bovine syndrome). Although this presentation mimicked artery to artery embolization, a large filling defect on transthoracic echo pointed to the heart as the embolic source. Surgical removal of the mass revealed a cardiac myxoma (CM).

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 29-year-old African American man with a past medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and marijuana abuse presented to the hospital with acute onset of right facial droop and right-sided weakness 5 h prior to hospital arrival. The patient stated that he was well until he became lightheaded and fell to the ground. When he tried to get up, he noticed the right-sided symptoms.

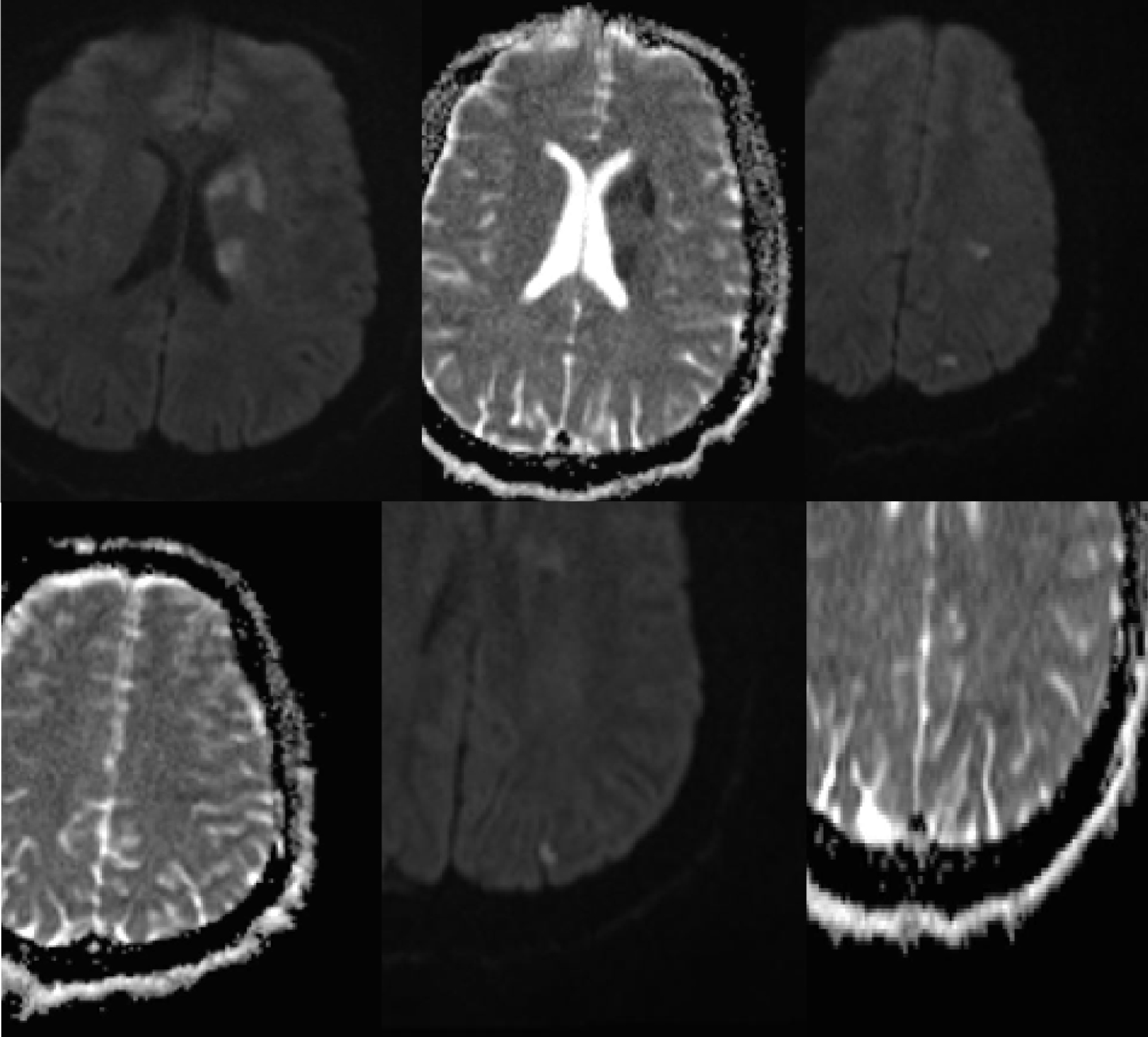

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were blood pressure 130/90, heart rate 80, respiratory rate 12, and temperature 37 °C. He appeared in general good health with no acute distress. His cardio-pulmonary physical exam was unremarkable. No heart murmur could be heard. There were no signs or symptoms of heart failure. National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 5 (right upper extremity weakness: 2, right lower extremity weakness: 1, dysarthria: 1, and right facial droop: 1). Admission labs were unremarkable except urine drug test, which was positive for marijuana. Electrocardiography (EKG) showed normal sinus rhythm. Head computed tomography (CT) without contrast was negative for any acute abnormalities. Carotid ultrasound did not show any evidence compatible with dissection. CT angiogram of the head and neck was negative for any stenosis, occlusion, dissection or atherosclerosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain without contrast revealed acute left hemispheric ischemic stroke in multiple vascular territories including internal capsule, basal ganglia and deep fronto-parieto-occipital area (Fig. 1). The patient was out of the window for tissue plasminogen activator and was admitted to the neurology service.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Multiple foci of diffusion restriction in the left hemisphere which are mostly in the basal ganglia and scattered in white matter of the frontal, parietal and occipital lobes. |

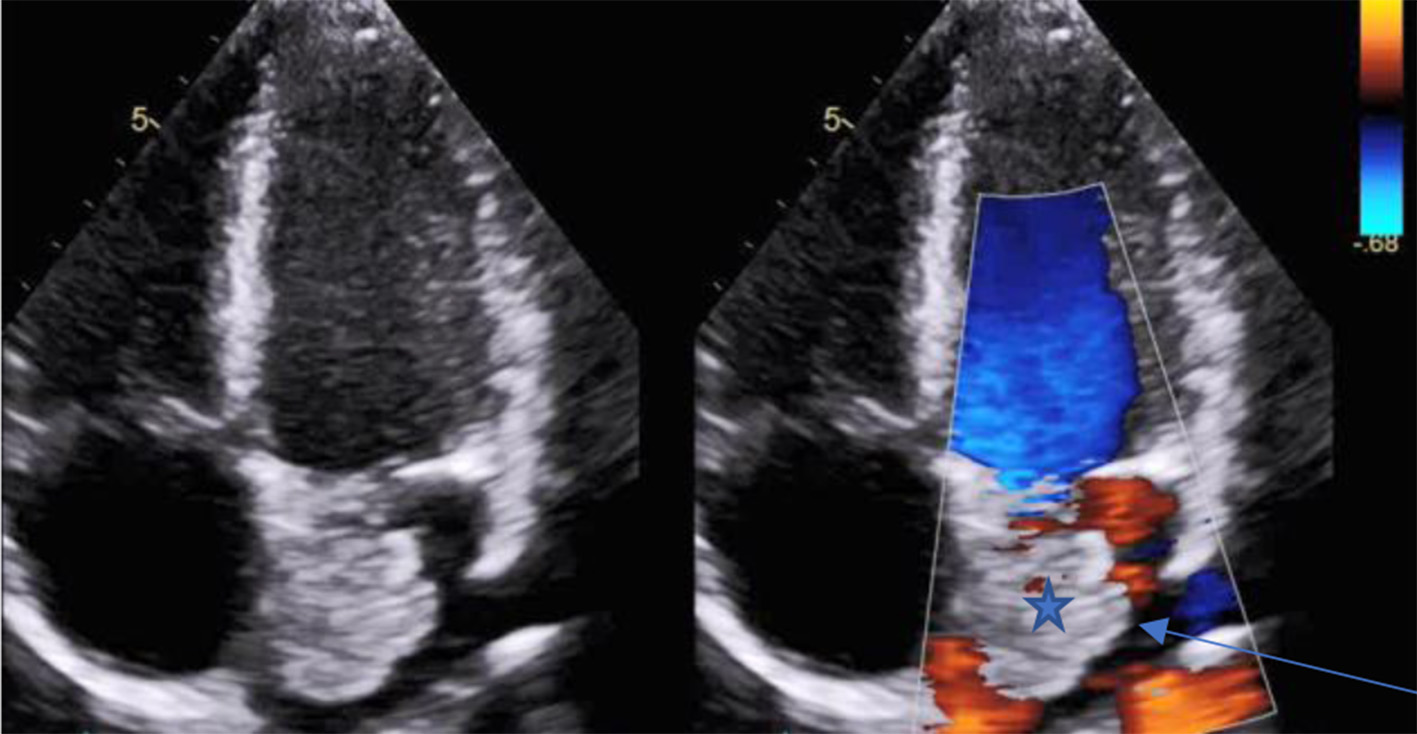

As part of his syncope workup in the emergency department (ED), the patient had a chest CT with contrast that showed a large filling defect attached to the left atrial wall. A bovine aortic arch was also identified (Fig. 2). Both transthoracic and trans-esophageal echocardiograms revealed a 2.1 × 2.6 cm mass consistent with an atrial myxoma (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Second most common subtype: common origin of innominate and left common carotid arteries. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Transesophageal echo shows a 2.1 × 2.6 cm mass consistent with an atrial myxoma (blue arrow). |

Six days following initial hospital presentation, the mass was successfully resected. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of atrial myxoma.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Typically, cardioembolic infarctions are bi-hemispheric in multiple vascular territories. This pattern may be altered by anatomic variations of the proximal arterial tree. For example, in patients with the bovine aortic arch, strokes are more likely confined to the left hemisphere [2].

In this report, we present a case with unilateral stroke in multiple vascular territories secondary to an unusual aortic arch anatomical variation.

The aortic arch may assume different patterns. The most common variant in humans with the prevalence of 65% in general population consists of three great vessels originating separately from the arch of the aorta [3-5, 8, 9]. In this standard aortic arch, the brachiocephalic artery (also known as the innominate) is the first branch off the arch with the largest calibre. It heads upward and parallel to the direction of the ascending aorta. The left common carotid artery arises as the second branch from the arch.

In the second most common pattern, the innominate and the left common carotid arteries branch from one trunk while the left subclavian branches separately (Fig. 2) [6].

In type three, the left common carotid artery originates directly from the innominate artery. Types two and three both are called a bovine variant which is a misnomer since these variants have no resemblance to the cattle’s aortic arch. The actual bovine syndrome is type four, where all the major vessels arise from a single trunk [3].

Based on visualization with CT angiography, our patient has type 2 aortic arch variant.

There are limited retrospective and prospective data regarding the relationship of strokes to aortic arch variants [2]. However, in 2013, Shadden et al studied the stroke hemispheric tendency in patients with different aortic arch types. They selected 10 patients with varying types of the aortic arch and injected embolic particles into the aortic valve. Their results indicated that aortic arch configuration might impact left vs. right embolic stroke. In particular, the type 2 bovine variant had a strong predilection to the left hemisphere, probably secondary to the acute angle between the left common carotid artery and aortic arch.

Our patient had a CM, which was diagnosed during this hospitalization and confirmed after the surgery. CMs occur most commonly in the fourth to seventh decades [10]. Although they are the most common benign primary heart tumors, they are quite rare. CMs mostly occur in the left atrium (75%), where they carry the potential to cause systemic emboli. Embolic events are common in 30-50% of patients with CMs. Cerebrovascular events (CVEs) comprise 50% of the embolic events related to CM. CM-related CVE is a very rare cause of the cerebrovascular accidents, accounting for about 0.5% of all strokes [10-12].

Stefanou et al reported one of the largest retrospective studies on patients with CM who presented with CVE [10]. In 46% of cases, an ischemic event occurred despite antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatment. In addition, 23% of patients developed recurrent emboli under bridging antithrombotic therapy prior to surgical excision.

Fortunately, in our case, the patient had prompt surgery with removal of the embolic source. He was discharged home with NIHSS 3 (right facial droop: 1, right upper extremity: 1, right lower extremity: 1). Prognosis is very good after surgery, the survival being 98% and 89% at 5 years and at 15 years, respectively [13].

Our case report emphasizes that a unilateral stroke may be cardioembolic, particularly in a young person. Care should be taken to include examination of the aortic arch when evaluating CT angiograms that are routinely performed of the intra- and extra-cranial vessels.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

AW supervised and finalized the manuscript; AHZM and RBS participated in the web search, writing and editing this manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Griffiths D, Sturm J. Epidemiology and etiology of young stroke. Stroke Res Treat. 2011;2011:209370.

doi pubmed - Shadden SC, et al. Embolic stroke hemispheric location is highly dependent of aortic arch and cerebral vessel configuration. Circulation. 2013;128:A14079.

- Layton KF, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, Lindell EP, Cox VS. Bovine aortic arch variant in humans: clarification of a common misnomer. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(7):1541-1542.

- Lippert H, Pabst R. Aortic arch. In: Arterial variations in man: classification and frequency. Munich, Germany: JF Bergmann-Verlag; 1985. p. 3-10.

doi - Deutsch L. Anatomy and angiographic diagnosis of extracranial and intracranial vascular disease. In: Rutherford RB, ed. Vascular Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa:Elsevier Saunders; 2005. p. 1916-1957.

- De Garis CF, Black IH, Riemenschneider EA. Patterns of the aortic arch in American white and negro stocks, with comparative notes on certain other mammals. J Anat. 1933;67(Pt 4):599-619.

- McDonald JJ, Anson BJ. Variations in the origin of arteries derived from the aortic arch, in American whites and Negroes. AmJ Phys Anthropol. 1940;27:91-107.

doi - Osborn AG. The aortic arch and great vessels. In: Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. p. 3-29.

- Shaw JA, Gravereaux EC, Eisenhauer AC. Carotid stenting in the bovine arch. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;60(4):566-569.

doi pubmed - Stefanou MI, Rath D, Stadler V, Richter H, Hennersdorf F, Lausberg HF, Lescan M, et al. Cardiac Myxoma and Cerebrovascular Events: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Neurol. 2018;9:823.

doi pubmed - Browne WT, Wijdicks EF, Parisi JE, Viggiano RW. Fulminant brain necrosis from atrial myxoma showers. Stroke. 1993;24(7):1090-1092.

doi pubmed - Yuan SM, Humuruola G. Stroke of a cardiac myxoma origin. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2015;30(2):225-234.

doi - Mustafa ER, Tudorascu DR, Giuca A, Toader DM, Foarfa MC, Puiu I, Istrate-Ofiteru AM. A rare cause of ischemic stroke: cardiac myxoma. Case report and review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2018;59(3):903-909.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.