| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Original Article

Volume 2, Number 3, June 2012, pages 99-103

Evaluation of the Effects of Aspirin and Warfarin Use on the Volume of Intracranial Non-Traumatic Hemorrhage and Mortality Rate

Gokhan Evcilia, Hakan Akb, e, Ulku Turk Boroc, Soner Yaycioglud

aBitlis State Hospital Neurology Clinic, Bitlis, Turkey

bBitlis State Hospital Neurosurgery Clinic, Bitlis, Turkey

cDr. Lutfi Kirdar Kartal Research and Teaching Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

dNeurosurgery Department, Adnan Menderes University, School of Medicine, Aydin, Turkey

eCorresponding author: Hakan Ak

Manuscript accepted for publication April 18, 2012

Short title: Evaluation of Effects of Aspirin and Warfarin

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jnr100w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: To evaluate the effects of aspirin and warfarin use on the volume of intracranial hemorrhage and mortality rates.

Methods: The patients using aspirin and warfarin with intracranial non-traumatic hemorrhage were enrolled the study. Control group included the patients with intracerebral non-traumatic hemorrhage but not using any oral antiaggregant or anticoagulant agent. This is an open, prospective and controlled study. In the statistical analysis, chi-square test, T test, non-parametrical Mann Whitney U test, and Pearson’s coefficient of correlation were used.

Results: Total 104 hospitalized patients with intracranial hemorrhage were enrolled to the study, 47 (45%) of them were using aspirin or warfarin and 57 (55%) were not using. Mean age was 66.5 (± 12.04), 38 patients (36.5%) were using aspirin and 9 (8.65%) were using warfarin. At the end of eight months 10 (26.3%) patients using aspirin, 5 patients (55.6%) using warfarin, and 16 (26%) patients in the control group died. There was a statistically important difference between patients using aspirin/warfarin and control group (P < 0.05) in the hemorrhage volume. Aspirin or warfarin use did not have any effect on mortality rates (P > 0.05). Hemorrhages with ventricular extension did not have any significant effect on hemorrhage volume or mortality rate.

Conclusion: Aspirin and warfarin use increases hemorrhage volume in a statistically significant ratio, however no significant effect on mortality rate.

Keywords: Aspirin; Warfarin; Intracranial hemorrhage; Mortality; Ventricular extension

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cerebrovascular events (CVE) are an important cause of very high health costs all around the world and lead to important morbidity and mortality rates. It is the third most common cause of morbidity and mortality after coronary heart diseases and cancers. CVEs compromise about 20% of all neurological diseases and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) accounts for 10% to 15% of strokes [1-5], 30-day mortality rate of intracerebral hemorrhage is about 50% [5].

Some possible risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) include hypertension, advanced age, male gender, high alcohol intake, and diabetes [1, 2, 4, 6-16]. Determination of frequent risk factors with extended epidemiological studies and introducing of modifiable, reducible, and unknown risk factors in a population is the most important preventive approach.

The aim of our study is to evaluate the effects of aspirin and warfarin use on the hemorrhage volume and mortality rates and also to evaluate the effects of some risk factors on hemorrhage volume in patients with spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Patient selection

This study was performed in 2009 between January 1 and august 31 in Dr. Lutfi Kirdar Kartal Teaching and Research Hospital neurology clinic. Patients who were hospitalized due to spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage were enrolled. This is an open, prospective, and controlled study. Patients divided in to two groups, first group enrolled the patients using aspirin or warfarin. Second group is the control group having hemorrhage but not using any anti-aggregant or anti-coagulant agent. We evaluate the effects of aspirin and warfarin on mortality, hemorrhage volume, and involvement of ventricles.

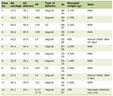

We used a pre-prepared form including age of the patient, gender, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia, liver and renal function tests and lipid levels in blood at the application time, history of aspirin or warfarin usage, INR (International Normalised Ratio) level for patients using warfarin, hemorrhage volume and site of bleeding for gathering data. We received information about deaths after 8 months by calling the family of patients with phone (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Relationship Between Some Causative Factors and Death |

Patients having subarachnoid hemorrhage, epidural or subdural hematoma, ICH secondary to arteriovenous malformation were not included in the study. Also, patients having vasculitis, coagulopathy, and tumor excluded from the study.

Lesions were detected with brain computed tomography (CT) and their locations, volumes and involvement of ventricles were recorded.

Radiological evaluation

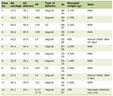

All patients underwent brain CT examination in the first 24 - 48 hours. Using these tomographies, site, volume, and ventricular extension of bleeding was recorded to our pre prepared form. Bleeding were divided in to four groups according to site; lobar, deep located (thalamic, putaminal, thalamo-putaminal), cerebellar, and brain stem (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Relationship Between Aspirin or Warfarin Use and Site of Bleeding, and Ventricular Extension |

To calculate the hematoma volume, the formula ABC/2 was used, where A is the greatest hemorrhage diameter by CT, B is the diameter 90o to A, and C is the approximate number of CT slices with hemorrhage multiplied by the slice thickness. Calculated values recorded without classification.

Statistical analysis

The effects of social and demographic characteristics like gender, age on risk factors was been evaluated besides of frequency of distribution. The relationship between usage of aspirin or warfarin with the hemorrhage volume was been evaluated. The effect of variables like hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia on hemorrhage volume was examined. Also, the presence of ventricular extension and site of bleeding in patients using aspirin or warfarin were evaluated.

In the statistical analysis of the variables which determined by ratio, namely in the comparison of the categorical data, chi-square test was used. In the analysis of the measured variables, T test was used when normal distribution was seen, and non-parametrical Mann Whitney U test was used when normal distribution was not seen was performed. Pearson’s coefficient of correlation was used to determine the relation of the measured variables. Data was gathered from patient folders and analysis was performed by SPSS 11.05 statistical software package. Significance level was determined as < 0.05.

| Results | ▴Top |

Hospitalized 104 patients having spontaneous ICH were enrolled in the study, 50 of them (48.1%) were female and 54 (51.9%) were male. Mean age was 66.5 (±12.04), 38 (36.5%) patients were using aspirin and 9 (8.65%) were using warfarin. Totally, 31 of all patients (29.8%) died during eight months, 15 of 47 (32%) patients using aspirin or warfarin (10 of 38 patients using aspirin, 5 of 9 patients using warfarin) died. In the control group 16 of 57 patients (28%) died. There was not a statistically significant difference between two groups (P > 0.05).

Ninety-two of all patients (88.4%) had hypertension (HT), 35 of patients (92%) using aspirin and all patients using warfarin had HT, 26 of all patients (25%) had diabetes mellitus (DM). Respectively, 13 and 2 of patients using aspirin and warfarin had DM, 29 of all patients (27.9%) had hyperlipidemia (HL), 13 patients using aspirin and 3 patients using warfarin had HL.

There was a ventricular extension of bleeding in 25 of all patients (24%).Ventricular extension was detected in 11 (28.9%) and 2 of patients using aspirin and warfarin, respectively. In the control group, ventricular extension was seen 12 patients (21%). There was not a statistically significant difference between two groups (P >0.05).

Mortality rate in hemorrhages with ventricular extension was 32%, however this rate was 29.1% in patients with no ventricular extension. There was no statistically significant difference between two groups (P > 0.05). Mortality rate was 29.3% in hypertensive patients and 33.3% in non-hypertensive patients, so there was no significant difference (P > 0.05). Mortality rate was 23.1% in diabetic patients and 32.1% in non-diabetic patients (P > 0.05). Hyperlipidemia did not have any effect on mortality rate (P > 0.05).

Classification according to the site of bleeding for all patients was as follow, 24 (23.1%) lobar, 10 (9.6%) brain stem, 5 (4.8%) cerebellar, and 65 (62.5%) were deep located. Sites of bleeding in patients using aspirin were lobar in 11 (28.9%), brain stem in 4 (10.5%), cerebellar in 1 (2.6%), and deep located in 22 (57.9%) patients. Sites of bleeding in patients using warfarin as follws 4 lobar and 5 deep located. There was not as statistically significant difference between aspirin or warfarin usage and site of bleeding (P > 0.05). Also, gender did not have any significant effect on site (P > 0.05).

It was detected that hemorrhage volume was greater in patients using aspirin or warfarin than control patients (P < 0.05). However, INR value did not have effect on hemorrhage volume.

When looked at all patients, it was detected that mortality rate was 25% in lobar, 60% in brain stem, 29.2% in deep located hemorrhages. No death detected in cerebellar hemorrhages. In patients using aspirin, mortality rates as follows; 3 in lobar, 2 in brain stem, and 5 in deep located hemorrhages. There was no statistically significant difference between site of bleeding and mortality. We could not detect significant difference between aspirin usage, sites of bleeding, and mortality (P > 0.05). In patients using warfarin, we detected high mortality rate in deep located hemorrhages (P < 0.05).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study we evaluated the effect of usage of aspirin and warfarin on ICH hemorrhage volume and mortality. We detected a significant effect on hemorrhage volume but not on mortality.

There are only a few studies about the mortality rates in the long term after spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage [17-21]. In these studies, data about the mortality rates were based on deaths occurred in hospitalized period, after one month, or after 3 months. In a recent study, mortality rates was been evaluated in the first month and first year. Mortality rate was been found as 38.3% and 49.6 for the first month and first year, respectively [22]. However, this study didn’t compare the effects of aspirin and/or warfarin. Cantalapiedra et al [18] reported the annually mortality rate as 30%. In this study, authors also reported that higher mortality was seen in anti-platelet-treated patients (44.9%) than in anticoagulated patients (31.1%). Hanger et al [20] found that mortality rate in 28 days was 43% in patients with ICH. This rate was found in patients using warfarin and aspirin, respectively, as 53% and 43%. Saloheimo et al [21] reported that three-month mortality for ICH was 33% and they concluded that poor short-term outcomes and increased mortality might be related with the regular usage of aspirin in moderate doses before the onset of CVE. Flibotte et al [23] investigated the three-week mortality rate of warfarin usage and reported this rate as 35%. Some studies reported usage of anti-platelet agent as independent risk factor mortality [21, 24]. However, some studies declared no relation between usage of anti-platelet agent and mortality [25, 26].

In our study, eight-month mortality rate was 29.8% in all patients enrolled in the study. In aspirin users this ratio was 29.3% and 31.8% in warfarin users. Mortality ratios were as follow 29.8% in aspirin users, 55.6% in warfarin users, and 31.8 in patients using no medication. According to our study, there was no relationship between the mortality rate and usage of warfarin. However, our group containing warfarin treated patients were smaller (n = 9). Because of this reason it not possible for us to make a general comment about mortality rate and warfarin use. We also did not find any significant effect of aspirin on mortality. However, our mortality rates well correlated with studies originating from Europe and United States.

In some studies, ICH has been showed parallel relation with INR, however, ICH may be seen when INR is in normal limits [27-29]. It was reported that if an ICH was developed when INR less than 3, the presence of any underlying cause should be controlled [20]. It was found that ICH develops when INR is between 2.9 - 3.7 [30-32]. Flaherty et al [33] investigated the relationship between INR value and hemorrhage volume. They concluded that INR levels less than 3 did not cause increase in the volume of hemorrhage, however, values more than 3 caused significant increase in hemorrhage volume in patients using warfarin. Similarly, in our study, warfarin usage has been related with increased hemorrhage volume, however, we didn’t find any correlation between INR value and hemorrhage volume.

In a recent study, Hanger et al [20] reported that hemorrhage volume, site of bleeding, intraventricular involvement, and warfarin usage had a relation with mortality independently from each other.

Flibotte et al [23] reported that warfarin use did not increase hemorrhage volume in the first plane, but during hospitalization hemorrhage volume might increase which could lead to increased mortality. According to this study, warfarin use increases mortality twice. Again in this study, authors reported that warfarin use and INR value did not have any effect on hemorrhage volume [23]. Results of this study well correlate with ours.

Literature contains conflicting results about the mortality of ICH related with aspirin and warfarin use [17-21]. Aspirin usage increased hemorrhage volume in our study, however, did not have any effect on mortality. Some published reports show that hemorrhage volumes, site of bleeding, intraventricular extension, and warfarin use have significant effects on mortality [27, 30]. Many study have been reported the increased mortality in patients having hemorrhage with ventricular extension [6, 12, 20, 22, 34]. However, in our study hemorrhage with ventricular extension did not have any effect on mortality rates, our conflicting result may be due to small number of our study group.

Smajlovic et al [35] investigated effect of the site of bleeding on mortality. In this study mortality rates were as follow 22.8% in internal capsule/basal ganglia hemorrhages, 31.7% in lobar hemorrhages, 64.4% in multi-lobar hemorrhages, 15.8% in cerebellar hemorrhages, and 83.3 in brain stem hemorrhages. Anderson et al [17] reported the mortality rate as 100% in brain stem hemorrhages. Our results correlate with published results, however, no death was observed in our patients having cerebellar hemorrhages.

In conclusion, we observed that aspirin and warfarin use did not have effect on mortality rates, but had significant effect on hemorrhage volume. Literature contains conflicting results coming from different studies and our study also added conflicting results about mortality, hemorrhage volume, and ventricular involvement. Because of this reason, multi-centered further studies containing large number of patients will help to make general comments about these conflicting results.

Conflict of Interest

We have no conflict of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Anderson CS, Jamrozik KD, Broadhurst RJ, Stewart-Wynne EG. Predicting survival for 1 year among different subtypes of stroke. Results from the Perth Community Stroke Study. Stroke. 1994;25(10):1935-1944.

pubmed doi - Gorelick PB. Stroke prevention. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(4):347-355.

pubmed doi - Sacco RL, Benjamin EJ, Broderick JP, Dyken M, Easton JD, Feinberg WM, Goldstein LB, et al. American Heart Association Prevention Conference. IV. Prevention and Rehabilitation of Stroke. Risk factors. Stroke. 1997;28(7):1507-1517.

pubmed doi - Thompson DW, Furlan AJ. Clinical epidemiology of stroke. Neurol Clin. 1996;14(2):309-315.

pubmed doi - Kase CS, Kurth T. Prevention of intracerebral hemorrhage recurrence. Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2011;17(6):1304-1317.

- Cheung RT, Zou LY. Use of the original, modified, or new intracerebral hemorrhage score to predict mortality and morbidity after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34(7):1717-1722.

pubmed doi - Garraway WM, Whisnant JP. The changing pattern of hypertension and the declining incidence of stroke. JAMA. 1987;258(2):214-217.

pubmed doi - Graffagnino C, Gasecki AP, Doig GS, Hachinski VC. The importance of family history in cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1994;25(8):1599-1604.

pubmed doi - Hachinski V, Graffagnino C, Beaudry M, Bernier G, Buck C, Donner A, Spence JD, et al. Lipids and stroke: a paradox resolved. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(4):303-308.

pubmed doi - Iso H, Jacobs DR, Jr., Wentworth D, Neaton JD, Cohen JD. Serum cholesterol levels and six-year mortality from stroke in 350,977 men screened for the multiple risk factor intervention trial. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(14):904-910.

pubmed doi - Kanter MC, Sherman DG. Strategies for preventing stroke. Curr Opin Neurol Neurosurg. 1993;6(1):60-65.

pubmed - Karnik R, Valentin A, Ammerer HP, Hochfelner A, Donath P, Slany J. Outcome in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage: predictors of survival. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2000;112(4):169-173.

pubmed - Qureshi AI, Safdar K, Weil J, Barch C, Bliwise DL, Colohan AR, Mackay B, et al. Predictors of early deterioration and mortality in black Americans with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1995;26(10):1764-1767.

pubmed doi - Schwarz S, Hafner K, Aschoff A, Schwab S. Incidence and prognostic significance of fever following intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2000;54(2):354-361.

pubmed - Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, D'Agostino RB. Management of risk factors. Neurol Clin. 1992;10(1):177-191.

pubmed - Woo D, Sauerbeck LR, Kissela BM, Khoury JC, Szaflarski JP, Gebel J, Shukla R, et al. Genetic and environmental risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage: preliminary results of a population-based study. Stroke. 2002;33(5):1190-1195.

pubmed doi - Anderson CS, Chakera TM, Stewart-Wynne EG, Jamrozik KD. Spectrum of primary intracerebral haemorrhage in Perth, Western Australia, 1989-90: incidence and outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57(8):936-940.

pubmed doi - Cantalapiedra A, Gutierrez O, Tortosa JI, Yanez M, Duenas M, Fernandez Fontecha E, Penarrubia MJ, et al. Oral anticoagulant treatment: risk factors involved in 500 intracranial hemorrhages. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;22(2):113-120.

pubmed doi - Gonzalez-Duarte A, Cantu C, Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Barinagarrementeria F. Recurrent primary cerebral hemorrhage: frequency, mechanisms, and prognosis. Stroke. 1998;29(9):1802-1805.

pubmed doi - Hanger HC, Fletcher VJ, Wilkinson TJ, Brown AJ, Frampton CM, Sainsbury R. Effect of aspirin and warfarin on early survival after intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol. 2008;255(3):347-352.

pubmed doi - Saloheimo P, Ahonen M, Juvela S, Pyhtinen J, Savolainen ER, Hillbom M. Regular aspirin-use preceding the onset of primary intracerebral hemorrhage is an independent predictor for death. Stroke. 2006;37(1):129-133.

pubmed doi - Börü ÜT, Gül L, Taşdemir M. A hospital- based study on long term mortality and predictive factors after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage from Turkey. Neurology Asia 2009; 14: 11-14.

- Flibotte JJ, Hagan N, O'Donnell J, Greenberg SM, Rosand J. Warfarin, hematoma expansion, and outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2004;63(6):1059-1064.

pubmed - Roquer J, Rodriguez Campello A, Gomis M, Ois A, Puente V, Munteis E. Previous antiplatelet therapy is an independent predictor of 30-day mortality after spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol. 2005;252(4):412-416.

pubmed doi - Nilsson OG, Lindgren A, Brandt L, Saveland H. Prediction of death in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage: a prospective study of a defined population. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(3):531-536.

pubmed doi - Rosand J, Eckman MH, Knudsen KA, Singer DE, Greenberg SM. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(8):880-884.

pubmed doi - Kase CS, Robinson RK, Stein RW, DeWitt LD, Hier DB, Harp DL, Williams JP, et al. Anticoagulant-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 1985;35(7):943-948.

pubmed - Landefeld CS, Rosenblatt MW, Goldman L. Bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin: relation to the prothrombin time and important remediable lesions. Am J Med. 1989;87(2):153-159.

pubmed doi - Shields RW, Jr., Laureno R, Lachman T, Victor M. Anticoagulant-related hemorrhage in acute cerebral embolism. Stroke. 1984;15(3):426-437.

pubmed doi - Franke CL, de Jonge J, van Swieten JC, Op de Coul AA, van Gijn J. Intracerebral hematomas during anticoagulant treatment. Stroke. 1990;21(5):726-730.

pubmed doi - Fredriksson K, Norrving B, Stromblad LG. Emergency reversal of anticoagulation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1992;23(7):972-977.

pubmed doi - Levine M, Hirsh J. Hemorrhagic complications of long-term anticoagulant therapy for ischemic cerebral vascular disease. Stroke. 1986;17(1):111-116.

pubmed doi - Flaherty ML, Tao H, Haverbusch M, Sekar P, Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, Khatri P, et al. Warfarin use leads to larger intracerebral hematomas. Neurology. 2008;71(14):1084-1089.

pubmed doi - Steiner T, Diringer MN, Schneider D, Mayer SA, Begtrup K, Broderick J, Skolnick BE, et al. Dynamics of intraventricular hemorrhage in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: risk factors, clinical impact, and effect of hemostatic therapy with recombinant activated factor VII. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(4):767-773; discussion 773-764.

pubmed - Smajlovic D, Salihovic D, O CI, Sinanovic O, Vidovic M. Analysis of risk factors, localization and 30-day prognosis of intracerebral hemorrhage. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2008;8(2):121-125.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.