| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Review

Volume 7, Number 4-5, October 2017, pages 67-79

The Pivotal Neuroinflammatory, Therapeutic and Neuroprotective Role of Alpha-Mangostin

Seidu A. Richarda, b, e, Songping Zhengc, Zhaoliang Sua, Jing Gaod, Huaxi Xua

aDepartment of Immunology, Jiangsu University, 301 Xuefu Road, Zhenjiang 212013, China

bDepartment of Surgery, Volta Regional Hospital, PO Box MA-374, Ho, Ghana-West Africa

cDepartment of Neurosurgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, 37 Guo Xue Xiang Street, Chengdu 610041, China

dDepartment of Pharmacy, Jiangsu University, 301 Xuefu Road, Zhenjiang 212013, China

eCorresponding Author: Seidu A. Richard, Department of Immunology, Jiangsu University, 301 Xuefu Road, Zhenjiang 212013, Jiangsu, China

Manuscript submitted October 13, 2017, accepted October 20, 2017

Short title: Alpha-Mangostin in CNS

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jnr455w

- Abstract

- Introduction

- α-MG and Mitochondrial Energetic Metabolism

- α-MG and Microglia

- α-MG and Neurotransmitters

- α-MG and Autophagy

- α-MG and Apoptosis

- Neuroinflammatory Potentails of α-MG

- Inflammatory Signaling Pathways of α-MG

- Prostaglandin E2 and Cyclooxygenase Synthesis by α-MG

- Neuroprotective Effect of α-MG

- Conclusions

- References

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Alpha-mangostin (α-MG), one of the key xanthone derivatives, displays a multiplicity of curative qualities like antiinfective, anti-malarial, anticarcinogenic, antidiabetic actions as well as antioxidant properties. Furthermore, it has proven to have neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective features, of which the anticarcinogenic action is the most auspicious. Additionally, several in vitro and in vivo analyses confirm that α-MG partakes in the major stages of tumor growth: initiation, promotion, and progression. Nevertheless, α-MG services as an inhibitory agent that modulate various enzymes involved in the metabolic activation and excretion of carcinogens, resistance to oxidative damage, and attenuation of inflammatory response. Numerous studies have also implicated α-MG in central nervous system (CNS) disorders, among which neuroinflammatory disorders and brain cancer are cardinal. Based on these initial studies on α-MG, we reviewed the pivotal role of α-MG in neuroinflammatory disorders.

Keywords: Mangosteen; Alpha-mangostin; Neuroinflammation; Neuroprotection; Neurodegeneration

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) is classified under the family Clusiaceae and is recognized as “the queen of fruits” for its pleasant taste [1]. Currently, many food commodities such as dietary supplements, beverages are manufactured from mangosteen fruits are gradually gaining recognition because of their scientifically proven beneficial role in human well-being [1-3]. The pericarps of mangosteen over the years have been used in various countries in Asia for curative tenacities in disease such as abdominal disorder (e.g. pain, dysentery, and diarrhea), suppuration, infected wounds and chronic ulcers [2, 4]. This pericarp is proven to contain numerous key substances like tannin, xanthone, chrysanthemin, garcinone, gartanin as well as extra bioactive substances [2]. Studies [4, 5] have proven that numerous ingredients are encompassed in the fruit structure of mangosteen and very prominent among them are α-mangostin (α-MG), γ-mangostin (γ-MG) and β-mangostin (β-MG). These components of mangosteen, have varied medicinal potentials like anti-histamine action, blockage of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-pumping adenosine 5-triphosphate (ATP)ase, and anti-serotonin actions [5-8]. Other mangosteen xanthone derivatives includes, 8-hydroxycudraxanthone G, mangostingone, garcinone D, cudraxanthone G, 8-deoxygartanin, garcimangosone B, garcinone E, gartanin, 1-isomangostin, mangostinone, smeathxanthone A, tovophyllin A, 3-isomangostin 8-desoxygartanin and 9- hydroxycalabaxanthone [9-11].

One of the most copious xanthone derivatives from the pericarps of mangosteen is α-MG. It comprises of 78% of the mangosteen content and it is one of the most investigated chemopreventive phytochemicals [2]. It has proven to have a wide range of medicinal characteristic like antioxidant, antiinfective, anti-malarial, anticarcinogenic, and antidiabetic actions. Furthermore, it has proven to have neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective features, of which the anticarcinogenic action is the most auspicious [2, 12, 13]. Additionally, several in vitro and in vivo analyses confirm that α-MG partakes in the major stages of tumor growth: initiation, promotion, and progression. α-MG services as an inhibitory agent that modulate various enzymes involved in the metabolic activation and excretion of carcinogens, resistance to oxidative damage, and attenuation of inflammatory response [2]. Moreover, the blockade of cell proliferation via modulating cell cycle regulatory machinery, induction of apoptotic effects on damaged and transformed cells, and inhibition of angiogenic and metastatic processes of tumor cells makes it a potential suppressing agent [2]. For the purposes of our review, we will concentrate on the pivotal role of α-MG in neuroinflammatory disorders.

| α-MG and Mitochondrial Energetic Metabolism | ▴Top |

Studies [14, 15] have demonstrated that α-MG triggers mitochondrial membrane depolarization and cytochrome C secretion in PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells, which means that α-MG, stimulates programed cell death via the mitochondrial pathway. The type of the molecular processes associated with the secretion of cytochrome C which is a cardinal part of mitochondrial apoptotic pathway stimulation still remains a matter of debate [14]. Nevertheless, the mitochondrial permeability transition (mPT), a Ca2+-dependent undefined permeabilization mechanism, is frequently linked to this programed cell death. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) is built from a collection of antecedent proteins, whose action is controlled by Ca2+-binding spots on the matrix side of the inner membrane. The alternation of the mPTP from open to closed positions and vice versa aids in the secretion Ca2+ from the matrix in a physiological manner [14, 16]. Conversely, following gigantic Ca2+ buildup, pore opening leads to pathological effects [17]. The sensitivity of mPT to Ca2+ is significantly amplified by a variety of triggers and circumstances [14, 18]. Many studies [14, 19, 20] have proven that oxidative stress may lead to mitochondrial nonspecific permeability besides Ca2+ encumber.

It has been demonstrated in both theoretical and experimental observations that Ca2+ can augment the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Cadenas and Boveris [21] have demonstrated that addition of Ca2+ and complex III inhibitor (antimycin A) to rat heart mitochondria resulted in sharp augmentation of ROS production. They explained that this phenomenon could perhaps be as a resultant uncoupling effect [21]. Also in vitro experiments on isolated brain mitochondria revealed a melodramatic upsurge in generation of ROS by complex I when electron flow from NADH to coenzyme Q was inhibited by rotenone [14, 22]. Studies [14, 23] have demonstrated that in an extraordinary pattern of regulation, the aerobic metabolism, via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, reduces O2 to H2O, while amplifying ATP synthesis and sustains of ROS generation to concentrations obligatory for microdomain cell signaling. The key ROS generated by mitochondria is O2, which is transmuted to H2O2 by the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). Furthermore, H2O2 can be converted to OH chaperon by metal ions during the Fenton reaction [14]. Nevertheless, the principal origin of O2 is the semiubiquinone radical intermediate (QH) produced during the Q cycle at complex III, though rotenone and other complex I inhibitors also trigger O2 production [14, 24].

Martínez-Abundis et al [14] demonstrated that α-MG has incomplete protective anti-lipid peroxidation and anti-oxidative damaging effects on proteins. They detected a substantial amplification of peripheral H2O2 facilitated by α-MG as well as triggering the activation of aconitase, blockade of respiratory rates and the formation of unspecific mPT. They further stated that the silhouette for the blockade of TBARS generation by α-MG was coherent with impediment of oxidative modification of mitochondrial proteins. They therefore proposed that the upsurge in H2O2 generation and inhibition of mitochondrial energetic metabolism implies that concentration-dependent effect of α-MG on TBARS generation resulted in aconitase activity [14]. Consequently, the site of O2 production is pertinent in clarifying this contradictory effect. Nevertheless, in rotenone-inhibited complex I, the potential locus of O2 is on the matrix-protruding arm [25]. Thus, O2 generation by complex I is usually discharged into the mitochondrial matrix, before α-MG can be accrued in this compartment [14]. This phenomenon clarifies the irreversible aconitase inhibition pattern.

Martinez-Abundis et al [14] further revealed that α-MG blocked lipid and protein oxidation and at elevated levels, it similarly possesses damaging consequences on mitochondrial activities. A conceivable justification might be that, as it co-exists with several flavonoids, auto-oxidation of α-MG might produce semiquinone radicals and quinines reducing mitochondrial abilities. Furthermore, quinoid products from mangiferin, a glucosyl xanthone, have the ability to arylate protein thiol groups and to activate the mitochondrial mPT [14, 26]. Also, the interface between semiquinone radicals obtained from α-MG with oxygen usually leads to reoxidation of the quinone and generation of O2 both in the outer and in the inner sides of the internal mitochondrial membrane. Nevertheless, augmented oxidative stress stimulated by quinone-like products of α-MG might be associated with the detected mutilation of the active metabolism: extricated outcome, ADP-triggered respiration reticence and straight interface with complex IV concentration, likewise the stimulation of the absorbency modification [14].

It is proposed that a blockage on stage three respiration might specify a straight interface with the multiplexes of the respiratory chain. This hypothesis was established by quantifying cytochrome c oxidase action blocked by α-MG. Furthermore, the hydrophobic attributes of α-MG and the justification that BSA, and not CSA, blocked the consequence of this compound on mPT stimulation, implies a straight disquieting consequence on the lipidic domain of mitochondria [14]. Moreover, a study by Dorta et al [27] proved that specific flavonoids exercise an extricating activity in mitochondrial membranes. They indicated that the respiratory chain blockade by this flavonoid has also been linked to their redox action, resulting in the production of ROS, thus aiding in the stimulation of mPT. Salvi et al [28]demonstrated that polyphenols such as genistein, facilitated mPT through the production of ROS because it is able to interact with complex I or III in the respiratory chain which implies that α-MG has possible stimulatory role in amplifying penetrability effects in mitochondria. A study [14] has further demonstrated that mangiferin - a glucosyl xanthone -arguments the liability of calcium triggered penetrability modification in rat liver mitochondria. Nevertheless, another study indicated that quercetin blockes mitochondrial oxygen utilization and triggers calcium secretion via the opening of mPTP [14, 29]. This explains the mechanisms via which Ca2+-triggered penetrability modification such as O2 generation at the I locus of the respiratory chain as well as of specific electron outflow towards O2, beside the blockage of the electron transport at the level of the NADH dehydrogenase [14, 23].

| α-MG and Microglia | ▴Top |

Microglia is the local immune cells in the brain, principally involved in modulating foreign proteins, cell debris, and numerous antagonistic particles. Stimulation of microglia often leads to modification in cell morphology from a resting ramified shape to an amoeboid profile, associated with sustained secretion of inflammatory neurotoxic agents. Furthermore, stimulation of microglia is recognized as the hallmark of neuroinflammation since proinflammatory cytokines and free radicals are generated by microglia in reaction to neuronal injury or immunological disorders [30]. Studies [30, 31] has shown that based on the probability that microglial stimulation may start a cascade of activities resulting in advancement of neurodegeneration, and functions as a key element that initiate the beginning of the degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons, to block the microglial stimulation, associated dopaminergic neurodegeneration is now an interesting approach in Parkinson’s disease (PD) management. Nevertheless, inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1b, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF)-α, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were elevated in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of PD patients. Their elevation has further influence on neurons thus the triggering of advanced neurodegeneration [30, 32, 33].

Studies [30, 34, 35] have shown that α-synuclein, the key constituent of Lewy bodies can trigger neurodegeneration in the accumulated form and partake in microglial stimulation by augmented generation of proinflammatory cytokines, thus causing an assiduous and radical nigral neurodegeneration in PD. Furthermore, modulating the stimulated microglia produced by α-synuclein may be a key approach for the management of neurodegenerative syndromes. Hu et al [30] demonstrated that α-MG blocked the α-synuclein-stimulated proinflammatory cytokines generation, nitric oxide (NO) secretion as well as ROS in principal microglial cells. They further indicated that antioxidant α-MG could reduce α-synuclein-triggered ROS generation by blockade of NOX-1. They concluded that α-MG, which blocked microglial stimulation triggered by α-synuclein by aiming at NADPH oxidase, may be a therapeutic option in averting PD advancement [30].

| α-MG and Neurotransmitters | ▴Top |

Some neurotransmitters have demonstrated to mediate with α-MG during the pathogenesis of neuroinflammatory disorders. Keys among these neurotransmitters are 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), histamine, acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase), cholinesterase as well as β-amyloid accumulation.

Acid sphingomyelinase

Studies [36, 37] have proven that aSMase-ceramide pathway is stringently linked to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, which facilitates lipoprotein retention within early atheromata and accelerates lesion advancement. Studies [36, 38] have further confirmed that α-MG has inhibitory actions on aSMase as well as effective selectivity antagonistic action on neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase). Consequently, a very few amount α-MG cognates have been cloned, and initial structure-activity relationship analysis has been accomplished. Research [36, 39] has shown that the blockade action of benzophenone cognate70 is similar to that of α-MG, but the cytotoxicity is less than 1/10-corrugates. Structurally, the two prenyl adjacent chains are prerequisite to the secretion of effective and selective blockade action to anti-aSMase. Studies have shown that compound 71 devoid of C-2 prenyl group sustains its action but lessens its selectivity while compound 72 devoid of C-8 prenyl group keeps selectivity, but lessening action. Furthermore, the olefinic moiety is conceivably not obligatory for the anti-aSMase actions, but influence selectivity due to tetrahydro-derivative 12 preserves action, although its selectivity is decreased. Nevertheless, the free hydroxyl groups at C-3 and C-6 locations enhance the anti-aSMase action, which is authenticated by the indolence of diacetyl derivative 34 [36, 39].

Histamine (H1)

It is well established that histamine is one of the key intermediaries of inflammation. Studies have shown that α-MG possesses anti-inflammatory actions [7]. This was revealed in a study [40] involving the injection of α-MG intraperitoneally in normal and bilaterally adrenalectomized rats. These anti-inflammatory actions of α-MG were proved to be its resultant capability of antagonizing histamine H1 receptor. Normally, the structure of antihistamines comprises of at least one tertiary nitrogen group and an aromatic portion containing two phenyl rings. Almost every antihistamine contains synthetic nitrogen compounds such as pyrilamine, phenothiazine and chlorpheniramine [7]. Studies have shown that 4, 4'-diacetyl curcumin a non-nitrogenous compound blocks the actions of histamine on smooth muscle. This compound does not act on the cellular surface receptor sites for histamine, as most synthetic antihistamine drugs do [7]. BiSkesoy and Onaran [41] demonstrated that α-MG has lower affinity for the histamine H1 receptor as compared to chlorpheniramine, a typical histamine H I receptor antagonist (pA 2 8.3). Although the structure of α-MG does not look like antihistamines, α-MG possesses the histamine receptor blocking action and blocks directly to the histamine H l receptor sites. Therefore α-MG may be the first natural medication that can precisely antagonizes the histamine H1 receptor [7].

Cholinesterase

Davies and Maloney [42] are the first to put forth the “cholinergic hypothesis” which links learning and memory inabilities to substantial reduction in ACh concentration. It is interesting to note that the present typical medications for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are cholinesterase inhibitors. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) are two key categories of cholinesterase conscientious to the hydrolysis of ACh as well as controlling of cholinergic neurotransmission activities [36, 43]. It has been proven that [36] α-MG substantial blocks the actions of both AChE and BChE. Further investigations using molecular docking analyses proved convincingly that hydrogen bonding and π-σ interfaces at the functional location of these two enzymes may perhaps abet in their effectiveness. Studies have demonstrated that AChE intermediate in the dispensation and accumulation of Aβ peptide far above cholinergic actions, which is autonomous to its catalytic active site (CAS) as well as it inter-connection to peripheral anionic site (PAS) [36, 44]. Furthermore, α-MG though not very effective anti-AChE can function via inhibition of PAS enzyme and stimulate superfluous remunerations besides its blockade action [36, 45].

5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)

The neurotransmitter 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) partakes in various behavioral systems. The initiation of 5-HT2 receptors in the brain lead to hyperactivity syndromes like head-twitch response (HTR), resting tremor, head weaving and hypertonicity. The most comprehensively investigated behavioral models for the stimulation of 5-HT receptors in the central nervous system is HTR and 5-HT syndrome [46-49]. The 5-HT syndrome comprises of sequences of multifarious behavioral indicators that mostly embrace repetitive tramping of the forepaws, abduction of the hind limbs, Straub’s tail and resting tremor [46, 49]. The HTR and 5-HT syndrome can be induced in mice and rats by injecting 5-HT precursors, tryptophan or 5-HTP [46, 47, 49]. The injection of 5-HT receptor agonists will directly trigger 5-HT receptors like 5-methoxy-N, N dimethyltryptamine or D-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or by drugs that secretes 5-HT like fenfluramine [46, 48].

Studies [46, 50, 51] have shown that these two behavioral models of 5-HT receptor initiation correlate well with distinctive kinds of 5-HT receptor. The HTR in mice is meticulously linked to the activities of 5- HT2 receptors on postsynaptic neurones, while the 5-HT syndrome is linked to postsynaptic 5-HT1 receptors [46, 52]. The 5-HT2 receptors comprises of three distinctive subtypes such as 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C. Studies [46, 53, 54] have proven that HTR in mice or rats is the precise behavioral model for the stimulation of 5-HT2A receptors. Furthermore, studies [46, 53, 55] have demonstrated that intraperitoneal injection of 5-fluoro-a-methyltryptamine (5-FMT) triggers head-twitches via the stimulation of central 5-HT neurones. Moreover, studies [46, 53] have shown that monoamine oxidase-A blockade via 5-FMT may lead to an upsurge in intracellular concentrations of 5-HT followed by an upsurge in 5-HT secretion. This perhaps lead to an augmented activation of postsynaptic 5-HT2 receptors [53]. These discoveries signify that 5-FMT-treated animals can be used to investigate the action of 5-HT2 receptor antagonists on the postsynaptic 5-HT2 receptors. Recently, studies have demonstrated that γ-MG could be a selective antagonist for 5-HT2A receptors in smooth muscle and platelets [7, 46]. Interestingly γ-MG does not have a nitrogen atom but rather possesses marked 5-HT2A receptor blocking activity. Currently, no research data linking 5-HT2A receptors and α-MG exist, although several studies have linked 5-HT2A receptors and γ-MG. We therefore propose the new research on α-MG should be geared towards this direction.

β-amyloid

Studies [36, 56] have demonstrated that the generation and buildup of oligomeric masses of Aβ is a fundamental occurrence during the pathogenesis of AD. These masses are assumed to be the triggers of pathogenic cascade leading to neuronal loss and dementia [56]. Further studies have shown that inhibition of these Aβ-masses is a realistic treatment approach that can lessen and/or avert the advancement of AD. Current research has proven that α-MG exhibits substantial protective effect against neurotoxicity stimulated by Aβ-(1-40) or Aβ-(1-42) oligomers. Also, α-MG preserves natural morphology of mammalian neurons, enriches their natural biological activities as well as interrupts the extreme advancement of AD [36, 57]. The above attributed is possible because of α-MG’s capability to block the Aβ accumulation cascades. Studies have shown that toxic β-sheet-rich accumulated Aβ oligomers, later-stage Aβ fibrils and suppressor Aβ fibril effectors are usually responsible for the above actions [36].

| α-MG and Autophagy | ▴Top |

Autophagic cell death (ACD) is an imperative biological activity observed in all eukaryotic cells [58-62]. ACD is marked with substantial mortification of cellular constituents, such as parts of the cytoplasm and intracellular organelles via intricate intracellular membrane/vesicle reformation and lysosomal hydrolysis [58-60, 63]. Studies [58, 59] have shown that ACD is essential for growth as well as stress antiphons. Furthermore, it has been detected in numerous human disorders such as neurodegenerative, muscular disorders and defiance to pathogens. Moreover, comparable to apoptosis, ACD is inhibited in malignant cancers. Studies have demonstrated that autophagy is triggered in reaction to γ irradiation and several anticancer remedies, specifically in apoptosis-deficient cells [58, 63, 64]. Numerous molecular and cell-signaling pathways have been incriminated in controlling autophagy. These pathways include the BECN1, AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK), mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K-AKT-mTOR) pathways [58, 65]. Nevertheless, the comprehensive means via which autophagic cell-signaling pathway function is still a matter of debate although numerous authors have demonstrated that autophagy is activated in reaction to countless anticancer medications [58, 66, 67].

Chao et al [58] demonstrated that α-MG-triggered autophagy. They further explain that ACD was inhibited by 3-MA, Baf A1 as well as shRNA knockdown of beclin-1. Moreover, choosy knockdown of AMPK release by AMPK shRNA reduced α-MG-triggered autophagy. They again demonstrated that AMPK is responsible for indolent phosphorylation of raptor and relationship between raptor and the inhibitor 14-3-3γ, leading to mTORC1 blockade. Studies [58, 68, 69] have shown that serine or threonine kinase and Liver kinase B1 (LKB1), is the key controller of AMPK via phosphorylation of AMPK at the stimulation loop, precisely at threonine 172 of the α-subunit. Further studies [58, 68-70] have demonstrated that the stimulation of the LKB/AMPK pathway is related to autophagy. A study [71] has shown that mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) is a key controller of autophagy. The mTORC1 complex comprises of the scaffolding protein regulatory-related protein of mTOR (raptor), mammalian lethal Sec13 protein 8 (mLST8), proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa (PRAS40), and DEP-domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein (Deptor) [58, 71, 72]. Numerous authors [58, 73-75] have proven that stimulation of mTORC1 is controlled by diverse elements such as PI3K/AKT and AMPK. Furthermore, AMPK can phosphorylate raptor, which is then insulated by 14-3-3γ, leading to mTORC1 blockade [58, 75].

| α-MG and Apoptosis | ▴Top |

Studies [2, 76] have proven that there are typically two key apoptotic pathways which are; the extrinsic or death receptor pathway and the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway. It has been proven that the extrinsic pathway is stimulated when death ligands binds to death receptors on the cell surface resulting in the triggering of caspase-8. On the other hand, the intrinsic pathway is depicted with the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, resulting in the secretion of cytochrome c and caspase-9 stimulation [76]. Numerous authors [2, 77-79] have demonstrated that α-MG triggers apoptosis via both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways resulting in the stimulation of caspases-8, -9 and -3, in human hepatoma SK-Hep-1 cells, melanoma SK-MEL-28 cells and breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Furthermore, a study [80] also revealed the upregulation of Fas and tBid in human colorectal cancer COLO 205 cells. The suggested means via which α-MG-triggered apoptosis is in the various cancers above is explained below. Treatment of α-MG with the cell lines resulted in the stimulation of extrinsic pathway which in turn triggered procaspase-8 cleavage into caspase-8. This further leads to cleavage of Bid to tBid. The formed tBid then translocated to mitochondria leading to the stimulation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway [2, 80]. Studies [2, 81, 82] have proven that depletion of mitochondrial membrane potential results in reduction in intracellular ATP, downregulation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 and upregulation of antiapoptotic Bax, secretion of cytochrome c from mitochondria into cytosol, stimulation of the caspase cascade, and augmentation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage were the main events involved in the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is triggered by α-MG.

Numerous authors [83-85] believe that ROS is an interceder during apoptosis signaling. Furthermore, ROS are higher in cells experiencing apoptosis and antioxidants proven to safeguard neuronal cells against apoptosis triggered by a multiplicity of apoptotic mediators. Moreover, ROS trigger caspase-3 and caspase-3-like proteases in different cell categories including neuronal cells, resulting in nuclear compression and DNA disintegration [83, 86-89]. Nevertheless, ROS also trigger apoptosis, possibly by reducing secretion of Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic molecule [83, 90, 91]. Also, Bcl-2 and Bax may regulator the mitochondrial penetrability modification pore, which can instigate the movement of cytochrome c and some apoptosis-triggered dynamics that activate the stimulation of caspase cascade leading to apoptosis [83, 90]. Studies [83, 92] have proven that caspase-3 is associated with apoptotic activities happening in the mitochondrial-adjunct pathway, which are related to nuclear compression and DNA cleavage. Furthermore, studies [83, 93] have shown that caspase-3 also stimulates phosphatidylserine externalization from the internal to external leaflets of the plasma membrane. Another study [94] indicated that phosphatidylserine appearance on the external leaflet of the plasma membrane enhance its binding to annexin-V which is extensively detected in apoptosis.

Studies [83, 95] have proven that xanthone revolutionizes iodoacetate-triggered cell death in principal cultures of cerebellar granule neurons by decreasing ROS configuration. On the other hand, α-MG has proven to mitigate the neurotoxicity triggered by beta-amyloid oligomers in SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells and prime rat cerebral cortical neurons [57, 83, 96]. Studies [83, 97] have further demonstrated that the antioxidative feature of α-MG is perhaps interceded by its regulatory influence on the movement of glutathione peroxidase. Janhom et al [83] indicated in their study that α-MG salvages apoptosis in dopaminergic SHSY5Y cells induced with 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), a cellular model of PD. They argue further that cytoprotection of α-MG against MPP+-triggered apoptosis may be linked to the decrease in ROS formation, regulating the stability between pro- and antiapoptotic genes, as well as suppression of caspase-3 stimulation. They demonstrated that DNA staining and PI/annexin-V twofold staining reinforce the notion that α-MG safeguarded nuclear modifications and phosphatidylserine externalization triggered by MPP+ introduction in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Nevertheless, α-MG reduced caspase-3 stimulation, reduced Bax mRNA secretion, and amplified Bcl-2 mRNA secretion triggered by MPP+ in dopaminergic SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Nonetheless, a study revealed that cisplatin-triggered apoptotic death resulted in α-MG mitigated proliferation of p53 secretion triggered by cisplatin [83, 98]. Another study [99] established a correlation between p53 and Bcl-2 family members. Studies [83, 99] have further shown that proapoptotic Bax, straightforwardly triggered by p53, can withstand the antiapoptotic influences of Bcl-2, while p53 can straightforwardly block Bcl-2. Janhom et al [83] also observed that α-MG may decrease the influences of MPP+ on Bax and Bcl-2 secretion by mitigating p53 secretion. Additional studies [4, 83] have proven that xanthone also blocks brain-derived acidic sphingomyelinase, a protein that regulates apoptosis and cell development.

| Neuroinflammatory Potentails of α-MG | ▴Top |

Neuroinflammation is key component in the pathogenesis and advancement of neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, PD, frontotemporal dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple sclerosis [100-102]. Studies [101-104] have demonstrated that brains from patients with neurodegenerative disorders are depicted with distinct astrocytosis, stimulation of microglia and higher concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines. Further studies [101, 105, 106] have shown that peripheral injection of lipopolysaccharid (LPS) in mice triggers astrocyte and microglia stimulation as well as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and proinflammatory cytokines secretion in the brain. An in vitro study [107] revealed that α-MG suppresses IL-6 and IL-8 secretion in LPS-triggered human gingival fibroblasts. Nevertheless, studies [101, 108] have proven that IL-6, which was secreted after peripheral immune experimentation, binds to its receptor on brain endothelial cells resulting in upsurge of COX-2 secretion as well as prostaglandin synthesis.

Preclinical statistics and human analyses [101, 109, 110] revealed an imperative role of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of depression, mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) and brief hypoxia. Furthermore, studies [101, 109] have proven that IL-6 is not merely a biomarker of TBI or neuroinflammation but, an intermediator of pathophysiology as well as a key influential factor during neuroinflammatory reaction. Correspondingly, a study [111] has shown that COX-2-catalyzed prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) stimulation IL-6 through p38 mitogen-activated kinase (p38 MAPK) and protein kinase C (PKC). Catorce et al [101] also confirmed an upsurge in COX-2 secretion in the brain. The secretion according to them was principally from cells of blood vessels after LPS induction. Studies [108, 112, 113] have shown that this upsurge could probably be due to IL-6 binding to its receptor as well as intracellular signaling through the c-Jun N-terminal kinase or signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3) pathways. Furthermore, some authors [101, 114] have proven that morphological silhouette of microglia and Iba-1 immunoreactivity was not related to the resultant inflammatory mRNA silhouette after peripheral LPS injection in mice as demonstrated earlier. Nevertheless, Hu et al [30] observed that α-MG blocks ROS and proinflammatory cytokines generation in α-synuclein-triggered microglia in vitro.

| Inflammatory Signaling Pathways of α-MG | ▴Top |

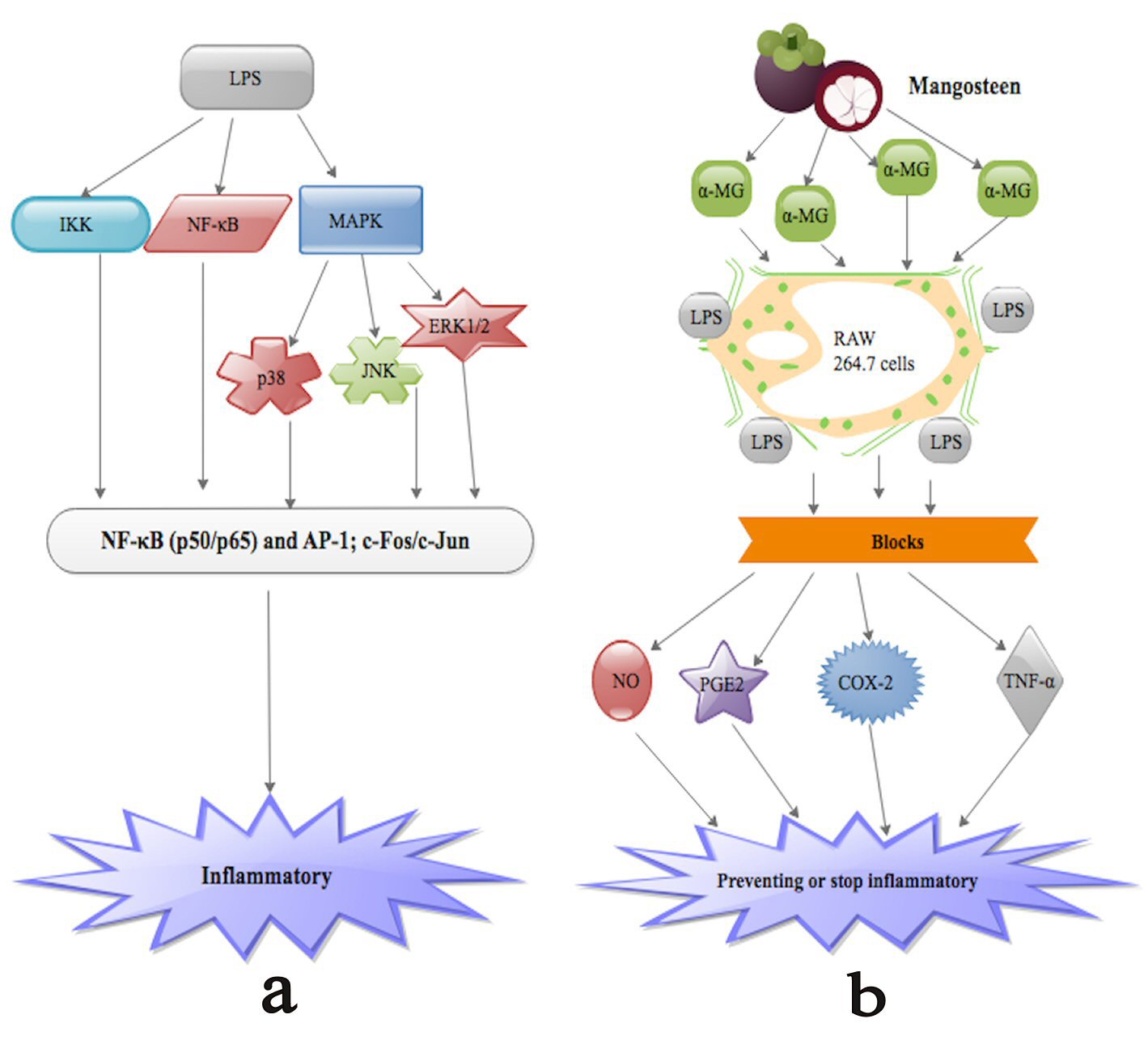

Studies [115, 116] have demonstrated that α-MG appreciably blocks NO, PGE2, TNF-α and iNOS generation in LPS-triggered RAW 264.7 cells (Fig.1b). PGE2, TNF-α and iNOS are cytokines implicated in inflammatory activities, such as amplified vascular penetrability, vascular dilation and neutrophil chemotaxis [115, 117]. Studies [115, 118] have further proven that LPS activation of human monocytes triggers numerous intracellular signaling pathways such as IκB kinase (IKK), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway as well as three MAPK pathways: extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 (Fig. 1a). These signaling pathways in turn trigger a multiplicity of transcription factors such as NF-κB (p50/p65) and activator protein 1 (AP-1; c-Fos/c-Jun), which synchronize the stimulation of numerous genes encoding inflammatory mediators [115, 118]. Nevertheless, the anti-inflammatory molecular consequence of α-MG is still a matter of debate.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) LPS activation of human monocytes triggers numerous intracellular signaling pathways such as IκB kinase (IKK), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway as well as three MAPK pathways: extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38. These signaling pathways in turn trigger a multiplicity of transcription factors such as NF-κB (p50/p65) and activator protein 1 (AP-1; c-Fos/c-Jun), which synchronize the stimulation of numerous genes encoding inflammatory mediators leading to inflammation. (b) α-MG appreciably blocks NO, PGE2, TNF-α and iNOS as well as COX-2 generation in LPS-triggered RAW 264.7 cells. |

| Prostaglandin E2 and Cyclooxygenase Synthesis by α-MG | ▴Top |

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) concentrations are extremely truncated or indiscernible in natural circumstances in the brain, nevertheless can be upsurge in inflammatory circumstances such as multiple sclerosis (MS), and AIDS-related dementia [5, 119, 120]. Excessive concentrations of PGE2 can interrupt the actions of numerous cell categories, comprising neurons, glial, endothelial cells as well as control microglia/macrophage and lymphocyte activities in inflammatory and immune circumstances [5, 121]. Consequently, the interaction between PGE2 and prevailing factors, such as pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, have prospective effect on the aftermath of inflammatory and immune reactions in the central nervous system (CNS). Several studies [5, 121] have proven that there is a strong relationship between the production of prostaglandins (PGs), inflammation, pain, and fever. Studies [5, 122] have further proven that glial cells, which are far more than neurons with a ratio of approximately 10:1 in the brain, offer mutual mechanical and metabolic sustenance of neurons. Glial cells are anticipated to be a key source of PGs in the CNS [122]. It is proposed [5] that modulation of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism, specifically PGE2 generation, seems advantageous in patients with inflammatory disorders. Nakatani et al [5] demonstrated that blockade of the 40% ethanol mangosteen extract on prostaglandin E2 synthesis is due to α-MG and γ-MG. Nevertheless, H2O extract of mangosteen might have unidentified constituents with inhibitory influence on PGE2 synthesis other than α-MG and γ-MG, since the extract that had no α-MG and γ-MG also blocked PGE2 synthesis.

On the other hand, cyclooxygenase (COX) which is rate-limiting enzyme in PG synthesis appears in two isoforms. These two isoforms are the constitutive (COX-1) and the inducible (COX-2). They are derived from different genes, but are structurally preserved [5, 123, 124]. It is proven [5] that COX-1 secretion is developmentally oriented. PGs generated via COX-1 predominantly partake in fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, gastric acid secretion, as well as platelet aggregation. However, COX-2 is secreted in reaction to inflammatory incitements. It is effective in biological reactions to growth factors and glucocorticoids [5, 125]. Navya et al [126] researched into the molecular interface between α-MG, iNOS and COX-2 using computer docking kits (Fig. 1b). They demonstrated that α-MG is a ligand against COX-2 and iNOS, correspondingly, and bound the two via hydrogen bond interface. They however did not indicate whether α-MG can directly act via COX-2 and iNOS [126]. Therefore, further studies are needed in this direction. Nevertheless, as a means responsible for iNOS and COX-2 blockade, α-MG has proven to trigger SIRT-1, a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide-dependent histone deacetylase [2]. Research [127] has shown that SIRT-1 substantially interrelates with the p65/RelA subunit of NF-κB and subdues NF-κB-driven gene transcription via deacetylating p65/RelA at lysine 310. Furthermore, the over secretion of ROS blocks SIRT-1 action via the induction of oxidative adjustments on its cysteine residues, thus augmenting NF-κB signaling leading to inflammatory reactions [2]. Moreover, α-MG nullified the acetylation of p65/NF-κB and NF-κB-modified proinflammatory gene secretion such as COX-2 and iNOS, via the stimulation of SIRT-1 in the U937 cell line [2, 128].

| Neuroprotective Effect of α-MG | ▴Top |

Research [129, 130] has testified that α-MG has numerous antioxidant qualities. Studies have proven that α-MG lowered the human low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation stimulated via copper or peroxyl radical. Studies [129, 131] have further proven that α-MG restrains the reduction of α-tocopherol depletion stimulated via LDL oxidation. Currently, studies [10, 129] have confirmed that α-MG is capable of scavenging peroxynitrite anion (ONOO-). Nevertheless, blockade of mitochondrial metabolism via the toxin 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP) has proven to trigger the initiation of ROS. Moreover, chronic inoculation of this toxin brought about some histopathological, neurochemical and motor modifications linked to Huntington’s disease in monkeys and rodents. These activities above incriminate mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders [129, 132, 133]. Several authors [129, 134, 135] have established that the production of ROS like superoxide anion (O2•-), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), and cellular oxidative mutilation occurs in rat striatum after inoculation of 3-NP. Interestingly, oxidative mutilation and the size of the striatal lesion triggered via 3-NP are decreased after antioxidant inoculation [129, 136].

Numerous studies [129, 137] have implicated augmented secretion of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in PC12 cells after 3-NP inoculation. Also, mitochondrial O2•- production have also been observed after the inoculation of 3-NP in alveolar bronchial epithelial cells [129, 138]. Nevertheless, ONOO- has also been implicated in 3-NP stimulated toxicity [129, 139]. All the above points to the fact that ROS generation and oxidative mutilation via 3-NP stimulated toxicity in neurons and several cell categories. Pedraza-Chaverr et al [129] demonstrated that α-MG has neuroprotective stimulus on 3-NP toxicity in a concentration-dependent manner. They further indicated that the neuroprotective properties of α-MG are possibly due to its capability of scavenging O2, O2•- and/or ONOO-. In confirmation, both O2•- and/or ONOO- have been implicated in 3-NP-triggered neurotoxicity [129, 134, 139]. Nonetheless, the neuroprotective influence of α-MG against 3-NP is linked with substantial amelioration of ROS generation which was quantifies using the fluorescent markers ethidium and carboxy-DCF. These finding above means that α-MG may be an auspicious multifunctional agent that could be used treat AD, because of its ability to scavenge ROS, metal-chelating, AChE and BChE blockades as well as Aβ accumulation- lessening potentials [36].

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

The anti-inflammatory potentials of α-MG in human cells were initially restricted to bacterial and some viral infections, malarial, cancer, and diabetes with little focus on neuroinflammatory disorders. It is currently well known that α-MG reduces LPS-triggered secretion of inflammatory genes. Additionally, α-MG has also proven to partake in mitochondrial energetic metabolism, microglia activation, autophagy as well as apoptosis in the CNS. Recent studies conducted on neuroinflammatory disorders revealed that α-MG is a promising coadjuvants for the treatment of neuroinflammatory disorders since these disorders may alter cellular metabolism of α-MG and perhaps rise its bioavailability which inturn reduce the inflammatory process. Furthermore, α-MG has also proven to possesse neuroprotective potential although further studies are still warranted to further elucidate these factors. This means that α-MG could become a very vital agent in preventing neuroinflammatory disorders.

Author Contributions

SAR is guarantors of integrity of the entire concepts and design. SAR wrote the final manuscript. SPZ contributed in literature search and draft of sections of the manuscript. ZS, JG and HX contributed equally to the intellectual content of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Source of Funding

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Garrity AR, Morton GA, Morton JC. Nutraceutical mangosteen composition. In.: US Patent 6,730,333; 2004.

- Zhang KJ, Gu QL, Yang K, Ming XJ, Wang JX. Anticarcinogenic effects of alpha-mangostin: A Review. Planta Med. 2017;83(3-04):188-202.

- Yeung S. Mangosteen for the cancer patient: facts and myths. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4(3):130-134.

doi pubmed - Pedraza-Chaverri J, Cardenas-Rodriguez N, Orozco-Ibarra M, Perez-Rojas JM. Medicinal properties of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana). Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(10):3227-3239.

doi pubmed - Nakatani K, Nakahata N, Arakawa T, Yasuda H, Ohizumi Y. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by gamma-mangostin, a xanthone derivative in mangosteen, in C6 rat glioma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63(1):73-79.

doi - Chairungsrilerd N, Furukawa KI, Ohta T, Nozoe S, Ohizumi Y. Gamma-mangostin, a novel type of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor antagonist. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357(1):25-31.

doi pubmed - Chairungsrilerd N, Furukawa K, Ohta T, Nozoe S, Ohizumi Y. Pharmacological properties of alpha-mangostin, a novel histamine H1 receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;314(3):351-356.

doi - Furukawa K, Shibusawa K, Chairungsrilerd N, Ohta T, Nozoe S, Ohizumi Y. The mode of inhibitory action of alpha-mangostin, a novel inhibitor, on the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-pumping ATPase from rabbit skeletal muscle. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1996;71(4):337-340.

doi pubmed - Raghavendra H, Kumar SP, Kekuda TP, Ramalingappa, Ejeta E, Mulatu K, Khanum F, Anilakumar K. Extraction and evaluation of alpha-mangostin for its antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Journal of Biologically Active Products from Nature. 2011;1(5-6):314-324.

doi - Jung HA, Su BN, Keller WJ, Mehta RG, Kinghorn AD. Antioxidant xanthones from the pericarp of Garcinia mangostana (Mangosteen). J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(6):2077-2082.

doi pubmed - Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. American journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1965;16(3):144-158.

- Shan T, Ma Q, Guo K, Liu J, Li W, Wang F, Wu E. Xanthones from mangosteen extracts as natural chemopreventive agents: potential anticancer drugs. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11(8):666-677.

doi pubmed - Ibrahim MY, Hashim NM, Mariod AA, Mohan S, Abdulla MA, Abdelwahab SI, Arbab IA. Alpha-Mangostin from Garcinia mangostana Linn: an updated review of its pharmacological properties. Arabian journal of Chemistry. 2016;9(3):317-329.

doi - Martinez-Abundis E, Garcia N, Correa F, Hernandez-Resendiz S, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Zazueta C. Effects of alpha-mangostin on mitochondrial energetic metabolism. Mitochondrion. 2010;10(2):151-157.

doi pubmed - Sato A, Fujiwara H, Oku H, Ishiguro K, Ohizumi Y. Alpha-mangostin induces Ca2+-ATPase-dependent apoptosis via mitochondrial pathway in PC12 cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95(1):33-40.

doi pubmed - Vergun O, Votyakova TV, Reynolds IJ. Spontaneous changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in single isolated brain mitochondria. Biophys J. 2003;85(5):3358-3366.

doi - Zoratti M, Szabo I. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241(2):139-176.

doi - Gunter TE, Pfeiffer DR. Mechanisms by which mitochondria transport calcium. Am J Physiol. 1990;258(5 Pt 1):C755-786.

pubmed - Halestrap AP, Woodfield KY, Connern CP. Oxidative stress, thiol reagents, and membrane potential modulate the mitochondrial permeability transition by affecting nucleotide binding to the adenine nucleotide translocase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(6):3346-3354.

doi pubmed - Bernardi P. Mitochondrial transport of cations: channels, exchangers, and permeability transition. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(4):1127-1155.

pubmed - Cadenas E, Boveris A. Enhancement of hydrogen peroxide formation by protophores and ionophores in antimycin-supplemented mitochondria. Biochem J. 1980;188(1):31-37.

doi pubmed - Votyakova TV, Reynolds IJ. Ca2+yakova TV, Reynolds IJ: xide formation by protophores and ionophores in antimycin-supplemented mitochondria affecting n. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005;93(3):526-537.

doi pubmed - Turrens JF. Superoxide production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biosci Rep. 1997;17(1):3-8.

doi pubmed - Brookes P, Darley-Usmar VM. Hypothesis: the mitochondrial NO(*) signaling pathway, and the transduction of nitrosative to oxidative cell signals: an alternative function for cytochrome C oxidase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32(4):370-374.

doi - Muller FL, Liu Y, Van Remmen H. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):49064-49073.

doi pubmed - Pardo-Andreu GL, Dorta DJ, Delgado R, Cavalheiro RA, Santos AC, Vercesi AE, Curti C. Vimang (Mangifera indica L. extract) induces permeability transition in isolated mitochondria, closely reproducing the effect of mangiferin, Vimang's main component. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;159(2):141-148.

doi pubmed - Dorta DJ, Pigoso AA, Mingatto FE, Rodrigues T, Prado IM, Helena AF, Uyemura SA, et al. The interaction of flavonoids with mitochondria: effects on energetic processes. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;152(2-3):67-78.

doi pubmed - Salvi M, Brunati AM, Clari G, Toninello A. Interaction of genistein with the mitochondrial electron transport chain results in opening of the membrane transition pore. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1556(2-3):187-196.

doi - Ortega R, Garcia N. The flavonoid quercetin induces changes in mitochondrial permeability by inhibiting adenine nucleotide translocase. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009;41(1):41-47.

doi pubmed - Hu Z, Wang W, Ling J, Jiang C. alpha-Mangostin Inhibits alpha-Synuclein-Induced Microglial Neuroinflammation and Neurotoxicity. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36(5):811-820.

doi pubmed - Ulusoy A, Bjorklund T, Buck K, Kirik D. Dysregulated dopamine storage increases the vulnerability to alpha-synuclein in nigral neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;47(3):367-377.

doi pubmed - Montgomery SL, Bowers WJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and the roles it plays in homeostatic and degenerative processes within the central nervous system. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7(1):42-59.

doi pubmed - Blum-Degen D, Muller T, Kuhn W, Gerlach M, Przuntek H, Riederer P. Interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's and de novo Parkinson's disease patients. Neurosci Lett. 1995;202(1-2):17-20.

doi - Sanchez-Guajardo V, Barnum CJ, Tansey MG, Romero-Ramos M. Neuroimmunological processes in Parkinson's disease and their relation to Alpha-synuclein: microglia as the referee between neuronal processes and peripheral immunity. ASN neuro. 2013;5(2):AN20120066.

doi pubmed - Zhang W, Wang T, Pei Z, Miller DS, Wu X, Block ML, Wilson B, et al. Aggregated alpha-synuclein activates microglia: a process leading to disease progression in Parkinson's disease. FASEB J. 2005;19(6):533-542.

doi pubmed - Wang MH, Zhang KJ, Gu QL, Bi XL, Wang JX. Pharmacology of mangostins and their derivatives: A comprehensive review. Chin J Nat Med. 2017;15(2):81-93.

doi - Devlin CM, Leventhal AR, Kuriakose G, Schuchman EH, Williams KJ, Tabas I. Acid sphingomyelinase promotes lipoprotein retention within early atheromata and accelerates lesion progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(10):1723-1730.

doi pubmed - Okudaira C, Ikeda Y, Kondo S, Furuya S, Hirabayashi Y, Koyano T, Saito Y, et al. Inhibition of acidic sphingomyelinase by xanthone compounds isolated from Garcinia speciosa. J Enzyme Inhib. 2000;15(2):129-138.

doi pubmed - Hamada M, Iikubo K, Ishikawa Y, Ikeda A, Umezawa K, Nishiyama S. Biological activities of alpha-mangostin derivatives against acidic sphingomyelinase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13(19):3151-3153.

doi - Gopalakrishnan C, Shankaranarayanan D, Kameswaran L, Nazimudeen SK. Effect of mangostin, a xanthone from Garcinia mangostana Linn. in immunopathological & inflammatory reactions. Indian J Exp Biol. 1980;18(8):843-846.

pubmed - Bokesoy TA, Onaran HO. Atypical Schild plots with histamine H1 receptor agonists and antagonists in the rabbit aorta. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;197(1):49-56.

doi - Davies P, Maloney AJ. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1976;2(8000):1403.

doi - Giacobini E. Cholinesterase inhibitors: new roles and therapeutic alternatives. Pharmacol Res. 2004;50(4):433-440.

doi pubmed - Rouleau J, Iorga BI, Guillou C. New potent human acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the tetracyclic triterpene series with inhibitory potency on amyloid beta aggregation. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46(6):2193-2205.

doi pubmed - Khaw KY, Choi SB, Tan SC, Wahab HA, Chan KL, Murugaiyah V. Prenylated xanthones from mangosteen as promising cholinesterase inhibitors and their molecular docking studies. Phytomedicine. 2014;21(11):1303-1309.

doi pubmed - Chairungsrilerd N, Furukawa KI, Tadano T, Kisara K, Ohizumi Y. Effect of rilerd N, Furukawa KI, Tadano T, Kisara K, Ohizumi Y. Inhibitors and their molecular docking studiesn amyloid ystemof mangiferin, Vimang'. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;123(5):855-862.

doi pubmed - Corne SJ, Pickering RW, Warner BT. A method for assessing the effects of drugs on the central actions of 5-hydroxytryptamine. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1963;20:106-120.

doi pubmed - Grahame-Smith DG. Inhibitory effect of chlorpromazine on the syndrome of hyperactivity produced by L-tryptophan or 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine in rats treated with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Br J Pharmacol. 1971;43(4):856-864.

doi pubmed - Grahame-Smith DG. Studies in vivo on the relationship between brain tryptophan, brain 5-HT synthesis and hyperactivity in rats treated with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor and L-tryptophan. J Neurochem. 1971;18(6):1053-1066.

doi pubmed - Green AR, O'Shaughnessy K, Hammond M, Schachter M, Grahame-Smith DG. Inhibition of 5-hydroxytryptamine-mediated behaviour by the putative 5-HT2 antagonist pirenperone. Neuropharmacology. 1983;22(5):573-578.

doi - Godfrey P, McClue S, Young M, Heal D. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-stimulated inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in the mouse cortex has pharmacological characteristics compatible with mediation via 5-HT2 receptors but this response does not reflect altered 5-HT2 function after 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine lesioning or repeated antidepressant treatments. J Neurochem. 1988;50(3):730-738.

doi pubmed - Lucki I, Nobler MS, Frazer A. Differential actions of serotonin antagonists on two behavioral models of serotonin receptor activation in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;228(1):133-139.

pubmed - Tadano T, Neda M, Hozumi M, Yonezawa A, Arai Y, Fujita T, Kinemuchi H, et al. alpha-Methylated tryptamine derivatives induce a 5-HT receptor-mediated head-twitch response in mice. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34(2):229-234.

doi - Schreiber R, Brocco M, Audinot V, Gobert A, Veiga S, Millan MJ. (1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4 iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane)-induced head-twitches in the rat are mediated by 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) 2A receptors: modulation by novel 5-HT2A/2C antagonists, D1 antagonists and 5-HT1A agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273(1):101-112.

pubmed - Kim SK, Toyoshima Y, Arai Y, Kinemuchi H, Tadano T, Oyama K, Satoh N, et al. Inhibition of monoamine oxidase by two substrate-analogues, with different preferences for 5-hydroxytryptamine neurons. Neuropharmacology. 1991;30(4):329-335.

doi - Glabe CG. Common mechanisms of amyloid oligomer pathogenesis in degenerative disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(4):570-575.

doi pubmed - Wang Y, Xia Z, Xu JR, Wang YX, Hou LN, Qiu Y, Chen HZ. Alpha-mangostin, a polyphenolic xanthone derivative from mangosteen, attenuates beta-amyloid oligomers-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting amyloid aggregation. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):871-881.

doi pubmed - Chao AC, Hsu YL, Liu CK, Kuo PL. alpha-Mangostin, a dietary xanthone, induces autophagic cell death by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase pathway in glioblastoma cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(5):2086-2096.

doi pubmed - Mizushima N, Levine B. Autophagy in mammalian development and differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(9):823-830.

doi pubmed - Puissant A, Robert G, Auberger P. Targeting autophagy to fight hematopoietic malignancies. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(17):3470-3478.

doi pubmed - Richard SA, Min W, Su Z, Xu H. High mobility group box 1 and traumatic brain injury. Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science. 2017;7(02):50.

doi - Seidu RA, Wu M, Su Z, Xu H. Paradoxical role of high mobility group box 1 in glioma: a suppressor or a promoter? Oncol Rev. 2017;11(1):325.

doi pubmed - Liu B, Cheng Y, Liu Q, Bao JK, Yang JM. Autophagic pathways as new targets for cancer drug development. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31(9):1154-1164.

doi pubmed - Kim KW, Moretti L, Mitchell LR, Jung DK, Lu B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress mediates radiation-induced autophagy by perk-eIF2alpha in caspase-3/7-deficient cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(22):3241-3251.

doi pubmed - Shaw RJ. LKB1 and AMP-activated protein kinase control of mTOR signalling and growth. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2009;196(1):65-80.

doi pubmed - Geng Y, Kohli L, Klocke BJ, Roth KA. Chloroquine-induced autophagic vacuole accumulation and cell death in glioma cells is p53 independent. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(5):473-481.

pubmed - Bursch W, Ellinger A, Kienzl H, Torok L, Pandey S, Sikorska M, Walker R, et al. Active cell death induced by the anti-estrogens tamoxifen and ICI 164 384 in human mammary carcinoma cells (MCF-7) in culture: the role of autophagy. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17(8):1595-1607.

doi pubmed - Law BY, Wang M, Ma DL, Al-Mousa F, Michelangeli F, Cheng SH, Ng MH, et al. Alisol B, a novel inhibitor of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) ATPase pump, induces autophagy, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(3):718-730.

doi pubmed - Lee YK, Park SY, Kim YM, Kim DC, Lee WS, Surh YJ, Park OJ. Suppression of mTOR via Akt-dependent and -independent mechanisms in selenium-treated colon cancer cells: involvement of AMPKalpha1. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(6):1092-1099.

doi pubmed - Puissant A, Robert G, Fenouille N, Luciano F, Cassuto JP, Raynaud S, Auberger P. Resveratrol promotes autophagic cell death in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells via JNK-mediated p62/SQSTM1 expression and AMPK activation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):1042-1052.

doi pubmed - Ciuffreda L, Di Sanza C, Incani UC, Milella M. The mTOR pathway: a new target in cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10(5):484-495.

doi pubmed - Chen M, Gu J, Delclos GL, Killary AM, Fan Z, Hildebrandt MA, Chamberlain RM, et al. Genetic variations of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and clinical outcome in muscle invasive and metastatic bladder cancer patients. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(8):1387-1391.

doi pubmed - Suh Y, Afaq F, Khan N, Johnson JJ, Khusro FH, Mukhtar H. Fisetin induces autophagic cell death through suppression of mTOR signaling pathway in prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(8):1424-1433.

doi pubmed - Hu H, Chai Y, Wang L, Zhang J, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Lu J. Pentagalloylglucose induces autophagy and caspase-independent programmed deaths in human PC-3 and mouse TRAMP-C2 prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(10):2833-2843.

doi pubmed - Hong-Brown LQ, Brown CR, Kazi AA, Huber DS, Pruznak AM, Lang CH. Alcohol and PRAS40 knockdown decrease mTOR activity and protein synthesis via AMPK signaling and changes in mTORC1 interaction. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109(6):1172-1184.

doi - Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13(15):1899-1911.

doi pubmed - Hsieh SC, Huang MH, Cheng CW, Hung JH, Yang SF, Hsieh YH. alpha-Mangostin induces mitochondrial dependent apoptosis in human hepatoma SK-Hep-1 cells through inhibition of p38 MAPK pathway. Apoptosis. 2013;18(12):1548-1560.

doi pubmed - Wang JJ, Zhang W, Sanderson BJ. Altered mRNA expression related to the apoptotic effect of three xanthones on human melanoma SK-MEL-28 cell line. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:715603.

doi pubmed - Ibrahim MY, Mohd Hashim N, Mohan S, Abdulla MA, Abdelwahab SI, Kamalidehghan B, Ghaderian M, et al. Involvement of NF-kappaB and HSP70 signaling pathways in the apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 cells induced by a prenylated xanthone compound, alpha-mangostin, from Cratoxylum arborescens. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2193-2211.

doi pubmed - Watanapokasin R, Jarinthanan F, Nakamura Y, Sawasjirakij N, Jaratrungtawee A, Suksamrarn S. Effects of alpha-mangostin on apoptosis induction of human colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(16):2086-2095.

doi pubmed - Krajarng A, Nakamura Y, Suksamrarn S, Watanapokasin R. alpha-Mangostin induces apoptosis in human chondrosarcoma cells through downregulation of ERK/JNK and Akt signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(10):5746-5754.

doi pubmed - Lee HN, Jang HY, Kim HJ, Shin SA, Choo GS, Park YS, Kim SK, et al. Antitumor and apoptosis-inducing effects of alpha-mangostin extracted from the pericarp of the mangosteen fruit (Garcinia mangostana L.)in YD-15 tongue mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37(4):939-948.

doi pubmed - Janhom P, Dharmasaroja P. Neuroprotective Effects of Alpha-Mangostin on MPP(+)-Induced Apoptotic Cell Death in Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells. J Toxicol. 2015;2015:919058.

doi pubmed - Alexandre J, Batteux F, Nicco C, Chereau C, Laurent A, Guillevin L, Weill B, et al. Accumulation of hydrogen peroxide is an early and crucial step for paclitaxel-induced cancer cell death both in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(1):41-48.

doi pubmed - Rayner BS, Duong TT, Myers SJ, Witting PK. Protective effect of a synthetic anti-oxidant on neuronal cell apoptosis resulting from experimental hypoxia re-oxygenation injury. J Neurochem. 2006;97(1):211-221.

doi pubmed - Higuchi M, Honda T, Proske RJ, Yeh ET. Regulation of reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis and necrosis by caspase 3-like proteases. Oncogene. 1998;17(21):2753-2760.

doi pubmed - Richard SA, Xiang LH, Yun JX, Shanshan Z, Jiang YY, Wang J, Su ZL, et al. Carcinogenic and therapeutic role of high-mobility group box 1 in cancer: is it a cancer facilitator, a cancer inhibitor or both? World Cancer Research Journal. 2017;4(3):e919.

- Richard SA, Min W, Su Z, Xu H-X. Epochal neuroinflammatory role of high mobility group box 1 in central nervous system diseases. AIMS Molecular Science. 2017;4(2):185-218.

doi - Suwanjang W, Abramov AY, Govitrapong P, Chetsawang B. Melatonin attenuates dexamethasone toxicity-induced oxidative stress, calpain and caspase activation in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;138:116-122.

doi pubmed - Zeng G, Tang T, Wu HJ, You WH, Luo JK, Lin Y, Liang QH, et al. Salvianolic acid B protects SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells from 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced apoptosis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33(8):1337-1342.

doi pubmed - Hildeman DA, Mitchell T, Aronow B, Wojciechowski S, Kappler J, Marrack P. Control of Bcl-2 expression by reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):15035-15040.

doi pubmed - Lakhani SA, Masud A, Kuida K, Porter GA, Jr., Booth CJ, Mehal WZ, Inayat I, et al. Caspases 3 and 7: key mediators of mitochondrial events of apoptosis. Science. 2006;311(5762):847-851.

doi pubmed - Mandal D, Moitra PK, Saha S, Basu J. Caspase 3 regulates phosphatidylserine externalization and phagocytosis of oxidatively stressed erythrocytes. FEBS Lett. 2002;513(2-3):184-188.

doi - Lee SH, Meng XW, Flatten KS, Loegering DA, Kaufmann SH. Phosphatidylserine exposure during apoptosis reflects bidirectional trafficking between plasma membrane and cytoplasm. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(1):64-76.

doi pubmed - Reyes-Fermin LM, Gonzalez-Reyes S, Tarco-Alvarez NG, Hernandez-Nava M, Orozco-Ibarra M, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Neuroprotective effect of alpha-mangostin and curcumin against iodoacetate-induced cell death. Nutr Neurosci. 2012;15(5):34-41.

doi pubmed - Moongkarndi P, Srisawat C, Saetun P, Jantaravinid J, Peerapittayamongkol C, Soi-ampornkul R, Junnu S, et al. Protective effect of mangosteen extract against beta-amyloid-induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and altered proteome in SK-N-SH cells. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(5):2076-2086.

doi pubmed - Marquez-Valadez B, Maldonado PD, Galvan-Arzate S, Mendez-Cuesta LA, Perez-De La Cruz V, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Chanez-Cardenas ME, et al. Alpha-mangostin induces changes in glutathione levels associated with glutathione peroxidase activity in rat brain synaptosomes. Nutr Neurosci. 2012;15(5):13-19.

doi pubmed - Sanchez-Perez Y, Morales-Barcenas R, Garcia-Cuellar CM, Lopez-Marure R, Calderon-Oliver M, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Chirino YI. The alpha-mangostin prevention on cisplatin-induced apoptotic death in LLC-PK1 cells is associated to an inhibition of ROS production and p53 induction. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;188(1):144-150.

doi pubmed - Hemann MT, Lowe SW. The p53-Bcl-2 connection. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(8):1256-1259.

doi pubmed - Pasqualetti G, Brooks DJ, Edison P. The role of neuroinflammation in dementias. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15(4):17.

doi pubmed - Nava Catorce M, Acero G, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Fragoso G, Govezensky T, Gevorkian G. Alpha-mangostin attenuates brain inflammation induced by peripheral lipopolysaccharide administration in C57BL/6J mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2016;297:20-27.

doi pubmed - Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Latz E. Innate immune activation in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(7):463-477.

doi pubmed - Serrano-Pozo A, Mielke ML, Gomez-Isla T, Betensky RA, Growdon JH, Frosch MP, Hyman BT. Reactive glia not only associates with plaques but also parallels tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(3):1373-1384.

doi pubmed - McGeer PL, McGeer EG. The amyloid cascade-inflammatory hypothesis of Alzheimer disease: implications for therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(4):479-497.

doi pubmed - Biesmans S, Meert TF, Bouwknecht JA, Acton PD, Davoodi N, De Haes P, Kuijlaars J, et al. Systemic immune activation leads to neuroinflammation and sickness behavior in mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:271359.

doi pubmed - Hoogland IC, Houbolt C, van Westerloo DJ, van Gool WA, van de Beek D. Systemic inflammation and microglial activation: systematic review of animal experiments. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:114.

doi pubmed - Yiemwattana I, Kaomongkolgit R. Alpha-mangostin suppresses IL-6 and IL-8 expression in P. gingivalis LPS-stimulated human gingival fibroblasts. Odontology. 2015;103(3):348-355.

doi pubmed - Eskilsson A, Mirrasekhian E, Dufour S, Schwaninger M, Engblom D, Blomqvist A. Immune-induced fever is mediated by IL-6 receptors on brain endothelial cells coupled to STAT3-dependent induction of brain endothelial prostaglandin synthesis. J Neurosci. 2014;34(48):15957-15961.

doi pubmed - Yang SH, Gangidine M, Pritts TA, Goodman MD, Lentsch AB. Interleukin 6 mediates neuroinflammation and motor coordination deficits after mild traumatic brain injury and brief hypoxia in mice. Shock. 2013;40(6):471-475.

doi pubmed - Haapakoski R, Mathieu J, Ebmeier KP, Alenius H, Kivimaki M. Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1beta, tumour necrosis factor alpha and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:206-215.

doi pubmed - Fiebich BL, Schleicher S, Spleiss O, Czygan M, Hull M. Mechanisms of prostaglandin E2-induced interleukin-6 release in astrocytes: possible involvement of EP4-like receptors, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and protein kinase C. J Neurochem. 2001;79(5):950-958.

doi pubmed - Schiltz JC, Sawchenko PE. Distinct brain vascular cell types manifest inducible cyclooxygenase expression as a function of the strength and nature of immune insults. J Neurosci. 2002;22(13):5606-5618.

pubmed - Matsumura K, Cao C, Ozaki M, Morii H, Nakadate K, Watanabe Y. Brain endothelial cells express cyclooxygenase-2 during lipopolysaccharide-induced fever: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical studies. J Neurosci. 1998;18(16):6279-6289.

pubmed - Norden DM, Trojanowski PJ, Villanueva E, Navarro E, Godbout JP. Sequential activation of microglia and astrocyte cytokine expression precedes increased Iba-1 or GFAP immunoreactivity following systemic immune challenge. Glia. 2016;64(2):300-316.

doi pubmed - Liu SH, Lee LT, Hu NY, Huange KK, Shih YC, Munekazu I, Li JM, et al. Effects of alpha-mangostin on the expression of anti-inflammatory genes in U937 cells. Chin Med. 2012;7(1):19.

doi pubmed - Chomnawang MT, Surassmo S, Nukoolkarn VS, Gritsanapan W. Effect of Garcinia mangostana on inflammation caused by Propionibacterium acnes. Fitoterapia. 2007;78(6):401-408.

doi pubmed - Choi EM, Hwang JK. Effects of Morus alba leaf extract on the production of nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2 and cytokines in RAW264.7 macrophages. Fitoterapia. 2005;76(7-8):608-613.

doi pubmed - Guha M, Mackman N. LPS induction of gene expression in human monocytes. Cell Signal. 2001;13(2):85-94.

doi - Fretland DJ. Potential role of prostaglandins and leukotrienes in multiple sclerosis and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1992;45(4):249-257.

doi - Griffin DE, Wesselingh SL, McArthur JC. Elevated central nervous system prostaglandins in human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol. 1994;35(5):592-597.

doi pubmed - Weissmann G. Prostaglandins as modulators rather than mediators of inflammation. J Lipid Mediat. 1993;6(1-3):275-286.

pubmed - Minghetti L, Polazzi E, Nicolini A, Levi G. Opposite regulation of prostaglandin E2 synthesis by transforming growth factor-beta1 and interleukin 10 in activated microglial cultures. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;82(1):31-39.

doi - Williams CS, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase: why two isoforms? Am J Physiol. 1996;270(3 Pt 1):G393-400.

pubmed - Smith WL, Dewitt DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2. Adv Immunol. 1996;62:167-215.

doi - DeWitt DL, Meade EA. Serum and glucocorticoid regulation of gene transcription and expression of the prostaglandin H synthase-1 and prostaglandin H synthase-2 isozymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;306(1):94-102.

doi pubmed - Navya A, Nanda Kumar Y, Hari Prasad O, Santhrani T, Uma Maheswari Devi P. In vivo and in silico Analysis Divulges the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Alpha-Mangostin. Int J Appl Biotech Biochem. 2012;2:69-80.

- Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, Mayo MW. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23(12):2369-2380.

doi pubmed - Franceschelli S, Pesce M, Ferrone A, Patruno A, Pasqualone L, Carlucci G, Ferrone V, et al. A novel biological role of alpha-mangostin in modulating inflammatory response through the activation of SIRT-1 signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(11):2439-2451.

doi pubmed - Pedraza-Chaverri J, Reyes-Fermin LM, Nolasco-Amaya EG, Orozco-Ibarra M, Medina-Campos ON, Gonzalez-Cuahutencos O, Rivero-Cruz I, et al. ROS scavenging capacity and neuroprotective effect of alpha-mangostin against 3-nitropropionic acid in cerebellar granule neurons. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009;61(5):491-501.

doi pubmed - Williams P, Ongsakul M, Proudfoot J, Croft K, Beilin L. Mangostin inhibits the oxidative modification of human low density lipoprotein. Free Radic Res. 1995;23(2):175-184.

doi pubmed - Mahabusarakam W, Proudfoot J, Taylor W, Croft K. Inhibition of lipoprotein oxidation by prenylated xanthones derived from mangostin. Free Radic Res. 2000;33(5):643-659.

doi pubmed - Beal MF, Brouillet E, Jenkins BG, Ferrante RJ, Kowall NW, Miller JM, Storey E, et al. Neurochemical and histologic characterization of striatal excitotoxic lesions produced by the mitochondrial toxin 3-nitropropionic acid. J Neurosci. 1993;13(10):4181-4192.

pubmed - Brouillet E, Hantraye P, Ferrante RJ, Dolan R, Leroy-Willig A, Kowall NW, Beal MF. Chronic mitochondrial energy impairment produces selective striatal degeneration and abnormal choreiform movements in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(15):7105-7109.

doi pubmed - Kim GW, Chan PH. Involvement of superoxide in excitotoxicity and DNA fragmentation in striatal vulnerability in mice after treatment with the mitochondrial toxin, 3-nitropropionic acid. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(7):798-809.

doi pubmed - Santamaria A, Jimenez-Capdeville ME, Camacho A, Rodriguez-Martinez E, Flores A, Galvan-Arzate S. In vivo hydroxyl radical formation after quinolinic acid infusion into rat corpus striatum. Neuroreport. 2001;12(12):2693-2696.

doi pubmed - Kim GW, Copin JC, Kawase M, Chen SF, Sato S, Gobbel GT, Chan PH. Excitotoxicity is required for induction of oxidative stress and apoptosis in mouse striatum by the mitochondrial toxin, 3-nitropropionic acid. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20(1):119-129.

doi pubmed - Mandavilli BS, Boldogh I, Van Houten B. 3-nitropropionic acid-induced hydrogen peroxide, mitochondrial DNA damage, and cell death are attenuated by Bcl-2 overexpression in PC12 cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;133(2):215-223.

doi pubmed - Bacsi A, Woodberry M, Widger W, Papaconstantinou J, Mitra S, Peterson JW, Boldogh I. Localization of superoxide anion production to mitochondrial electron transport chain in 3-NPA-treated cells. Mitochondrion. 2006;6(5):235-244.

doi pubmed - Matthews RT, Yang L, Jenkins BG, Ferrante RJ, Rosen BR, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Beal MF. Neuroprotective effects of creatine and cyclocreatine in animal models of Huntington's disease. J Neurosci. 1998;18(1):156-163.

pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.