| Journal of Neurology Research, ISSN 1923-2845 print, 1923-2853 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Neurol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.neurores.org |

Original Article

Volume 1, Number 3, August 2011, pages 90-95

Hemorrhagic Sensorimotor Stroke: Spectrum of Disease

Adrià Arboixa, b, d, Arne Saßmannshausena, Luis García-Erolesc, Joan Massonsa, Olga Parrab

aCerebrovascular Division, Department of Neurology, Hospital Universitari del Sagrat Cor, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

bCIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CB06/06), Instituto Carlos III, Madrid,Spain

cUnit of Organization, Planning and Information Systems, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, Mataro, Barcelona, Spain

dCorresponding author: Adrià Arboix, Cerebrovascular Division, Department of Neurology, Hospital Universitari del Sagrat Cor, Universitat de Barcelona, Viladomat 288, E-08029 Barcelona, Spain

Manuscript accepted for publication July 26, 2011

Short title: Hemorrhagic Pure Sensorimotor Stroke

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jnr26w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: This study is aimed to describe the clinical characteristics of hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke based on data collected from a prospective hospital-based acute stroke registry.

Methods: Twelve patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke were identified, which accounted for 9% of all cases of pure sensorimotor stroke (n = 133) and 2.9% of intracerebral hemorrhage (n = 408) entered in the database.

Results: Patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor were more likely to have hypertension, sudden onset, headache, altered consciousness, and internal capsule and basal ganglia involvement than patients with sensorimotor stroke of ischemic origin. When compared with patients with hemorrhagic stroke, hypertension, presence of previous TIA, obesity, heavy smoking, and involvement of the internal capsule were significantly more frequent in patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke, whereas altered consciousness, basal ganglia, parietal topography and ventricular involvement were less frequent. In the multivariate analysis, altered consciousness (odds ratio 17.2) and basal ganglia involvement (odds ratio 10.3) were independent predictors of hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke.

Conclusions: Hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke is a very infrequent stroke syndrome. Altered consciousness at stroke onset may be a useful sign for distinguishing hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke from other causes of lacunar stroke. There are important differences between hemorrhagic sensorimotor strokeand the remaining intracerebral hemorrhages.

Keywords: Hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke; Lacunar stroke; Intracerebral hemorrhage; Stroke

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Sensorimotor stroke is a distinctive lacunar syndrome [1, 2]. Lacunar syndromes are usually caused by symptomatic lacunar infarctions [1-4]. In 5-20% of cases, however, sensorimotor stroke and other lacunar syndromes not due to lacunar infarctions also occur, mainly due to small intracerebral hemorrhages or large non-lacunar ischemic brain infarctions [5-8]. Despite the recognition of the hemorrhagic cause of lacunar syndromes, little is known about the frequency of sensorimotor stroke due to intracerebral hemorrhage or hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke in stroke registries, as well as their clinical characteristics in relation to the remaining cases of intracerebral hemorrhages and sensorimotor stroke of ischemic origin.

Our aim was to examine clinical features of hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke in patients included in a prospective hospital-based stroke registry, as well as to compare demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, neuroimaging data and outcome of patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke with those of ischemic sensorimotor stroke and the remaining patients with intracerebral hemorrhage.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Between January 1986 and December 2004, data of 3808 stroke patients admitted consecutively to the Department of Neurology of the Sagrat Cor Hospital (an acute-care 350-bed teaching hospital in the city of Barcelona) were collected prospectively in a stroke registry [9, 10].

Subtypes of stroke were classified according to the Cerebrovascular Study Group of the Spanish Neurological Society [11], which is similar to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Classification [12] and has been used in previous studies [3, 5, 9, 10]. Definitions of cerebrovascular risk factors and lacunar syndromes were previously reported [3, 5, 13]. Sensorimotor stroke was defined as a unilateral partial or complete paresis and/or sensory deficit involving at least two of the three areas (face, upper and/or lower limb) with no evidence of aphasia, apraxia and agnosia, or visual field deficit, eye movement disturbance, ataxia, or bilateral weakness.

For the purpose of this study, patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA), subarachnoid hemorrhage, spontaneous subdural hematoma and spontaneous epidural hematoma were excluded. There were 2703 patients with brain infarction, 121 of whom had ischemic sensorimotor stroke. The remaining 407 patients in the stroke registry had intracerebral hemorrhage, 12 of whom had hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke. Ischemic sensorimotor stroke occurred as a result of a lacunar infarction (n = 83), an atherothrombotic infarction (n = 17), a cardio-embolic infarction (n = 15), a brain infarction of unusual etiology (n = 1) or an infarction of unknown cause (n = 5). Sensorimotor stroke was attributed to a lacunar infarction when the lacunar syndrome correlated with a small size infarction (deep hypodense areas with a maximum diameter of 15 mm on no more than two adjacent 10-mm tomographic cuts) in the vascular territory of the perforating arteries or when the two computerized tomographic (CT) scans obtained during hospitalization were negative and in the absence of cortical ischemia, carotid stenosis or major source for cardio-embolic stroke. Prior to conducting the study, approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research of the hospital. Study subjects or their next-of-kin signed a permission to treat form on admission to the hospital.

All patients were admitted to the hospital within 48 hours of onset of symptoms. On admission, demographic characteristics, salient features of clinical and neurological examination and results of laboratory tests (blood cell count, biochemical profile, serum electrolytes and urinalysis), chest radiography, and twelve-lead electrocardiography were recorded. In all patients, brain CT scan was performed within this first week of hospital admission. In patients with negative results, a second CT scan was obtained during hospitalization, or the patients were studied using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Overall, 34.6% of patients were studied by angio-MRI.

Statistical methods

Demographic characteristics, clinical events and outcome of patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke and those with ischemic sensorimotor stroke and remaining patients with intracerebral hemorrhage were compared using the Studen’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square (χ2) test (with Yate’s correction when necessary) for categorical variables. Variables plus age (used as a continuous variable with a constant odds ratio for each year) and sex were subjected to multivariate analysis with a logistic regression procedure and forward stepwise selection if P < 0.10 after univariate testing. Sensorimotor stroke coded as ischemic = 0, hemorrhagic = 1 were the dependent variables. The effect of variables on the presence of hemorrhagic or ischemic sensorimotor stroke was studied in two multiple regression models in which ischemic and hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke were the dependent variables, respectively. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from the beta coefficients and standard errors. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

| Results | ▴Top |

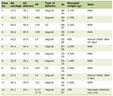

Hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke accounted for 9% of all cases of sensorimotor stroke (n = 133) and 2.9% of intracerebral hemorrhage (n = 408). There were 6 men and 6 women with a mean (SD) age of 75.6 (8.9) years. The characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Hypertension was found in 12 (100%) patients, heavy smoking in 3 (25%), obesity in 3 (25%) and previous TIA in 3 (25%). Dysarthria was present in 5 (41.7%) patients, headache in 3 (25%) and altered consciousness in 2 (16.7%). Involvement of the internal capsule was the most frequent topography (75%) followed by the basal ganglia (50%). At the time of hospital discharge, 11 patients had hemiparesis (mild in 7, moderate in 4) and only 1 patient was symptom free.

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical Data, Topography of Lesion, Neurological Findings and Outcome in 12 Patients With Hemorrhagic Sensorimotor Stroke |

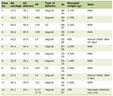

When the groups of patients with hemorrhagic and ischemic sensorimotor stroke were compared, hypertension, TIA, previous hemorrhagic stroke, obesity, sudden onset, headache at stroke onset, altered consciousness, and internal capsule and basal ganglia involvement were significantly more frequent in the hemorrhagic group (Table 2). For the comparison of hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke and the remaining patients with intracerebral hemorrhage, hypertension, TIA, obesity, heavy smoking, and internal capsule topography were significantly more frequent in patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke, whereas altered consciousness, basal ganglia and parietal topography, and ventricular involvement were significantly more common among the remaining patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (Table 2). In-hospital mortality was 0% in patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke and in patients with ischemic sensorimotor stroke compared with 28.3% in the group of the remaining patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (P = 0.042).

Click to view | Table 2. Comparison of Patients With Hemorrhagic Sensorimotor Stroke (SMS), Patients With Ischemic SMS and the Remaining Patients With Intracerebral Hemorrhage |

In the multivariate analysis, altered consciousness (OR = 17.2, 95% CI 2.2 - 133.3) and basal ganglia topography (OR = 10.3, 95% CI 2.6 - 40.8) were independent variables significantly associated with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke accounted for 9% sensorimotor strokes and 2.9% of intracerebral hemorrhages included in the stroke registry. Sensorimotor stroke is a clinical syndrome usually caused by symptomatic lacunar infarcts (62.4% of cases), showing that the lacunar hypothesis in pure motor stroke is clinically valid and useful. However, pathological heterogeneity in patients with sensorimotor stroke was found in 37.6% of patients, a percentage higher than 25% in the study of Gan et al [14]. Therefore, approximately in one of every three cases of sensorimotor stroke, this condition may be associated with an underlying non-lacunar infarct mechanism (ischemic: such as cardiac source of embolus, atherosclerosis, or hemorrhagic), which, in turn may influence management.

In a previous study [15], we found that lacunar syndrome not due to lacunar infarcts were mainly due to small intraparenchymatous hemorrhages or large subcortical infarcts. Moreover, 2.9% of intracerebral hemorrhages in our study presented as sensorimotor stroke. Classically, it was considered unlikely that intracerebral hemorrhage would cause a lacunar syndrome without other neurological manifestations, such as altered alertness, visual field defects, eye movement abnormalities or higher cortical dysfunction [1, 16]. However, Mori et al [17] in their study of 174 cases with recent intracerebral hemorrhage found 19 (10.9%) patients with lacunar syndrome and 7 (4%) presented sensorimotor stroke, a percentage higher to that fund in this study. Before the introduction of CT or MRI, it is likely that small hemorrhages producing lacunar syndrome might be misdiagnosed as lacunar infarctions. Therefore, it is very important to establish a definite aetiological diagnosis to allow a correct classification of sensorimotor stroke into the different stroke subtypes because of relevant therapeutic implications [3].

Hemorrhagic and ischemic sensorimotor stroke cannot be distinguished on the basis of semiological findings at the acute stage of stroke. The present results demonstrate a striking similarity between hemorrhagic and ischemic sensorimotor stroke. In the multivariate analysis, altered consciousness was the only clinical variable independently associated with the hemorrhagic variant. Accordingly, sensorimotor stroke in association with altered mental state at stroke onset was more likely to be of hemorrhagic origin.

The absence of in-hospital deaths indicates a favourable short-term prognosis in hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke [18, 19]. Finally, the presence of basal ganglia topography (50%) was another independent predictor of hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke, associated with internal capsule involvement (75%). In a previous study [20], we found that isolated capsular hemorrhage was associated with a higher frequency of lacunar syndromes (P < 0.05), mainly as pure motor hemiparesis (12.5% of cases) and sensorimotor stroke (8.5%) compared with other intracerebral hematomas, in which pure motor stroke occurred in only 2.9% of cases and sensorimotor stroke in 1.5%.

However, important clinical differences between hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke and the remaining cases of intracerebral hemorrhage were observed. Patients with hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke showed a higher frequency of internal capsule involvement as well as better outcome (no case of in-hospital death). This may be related to the small size of the lesion as opposed to the remaining patients with intracerebral hemorrhage who showed a higher frequency of altered consciousness, basal ganglia and parietal topography, and ventricular involvement which is consistent with large size of the lesion and a more frequent cortical topography of the hematoma [16, 21].

Conclusion

In summary, hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke is an infrequent syndrome and accounted for 9% of all cases of lacunar sensorimotor stroke and 2.3% of all cases of intracerebral hemorrhage. The presence of altered consciousness at stroke onset may be a useful sign for distinguishing hemorrhagic from ischemic sensorimotor stroke. There are important differences between hemorrhagic sensorimotor stroke and the remaining intracerebral hemorrhages.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs C. Targa, E. Comes, M. Balcells, M. Oliveres, M. Grau-Olivares, L. Blanco, A. Vicens and J.M. Vives for their assistance in this study and Dr Marta Pulido for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

Disclosure of Sources of Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS PI/081514), Instituto de Investigación Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

| References | ▴Top |

- Arboix A, Marti-Vilalta JL. Lacunar stroke. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(2):179-196.

pubmed doi - Fisher CM: Lacunar infarcts. A review. Cerebrovasc Dis 1991; 1: 311−320.

- Arboix A, Oliveres M, Garcia-Eroles L, Comes E, Balcells M, Targa C. Risk factors and clinical features of sensorimotor stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16(4):448-451.

pubmed doi - Chimowitz MI, Furlan AJ, Sila CA, Paranandi L, Beck GJ. Etiology of motor or sensory stroke: a prospective study of the predictive value of clinical and radiological features. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(4):519-525.

pubmed doi - Arboix A, Garcia-Eroles L, Massons J, Oliveres M, Balcells M. Haemorrhagic pure motor stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(2):219-223.

pubmed - Anzalone N, Landi G. Non ischaemic causes of lacunar syndromes: prevalence and clinical findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52(10):1188-1190.

pubmed doi - Boiten J, Lodder J. Lacunar infarcts. Pathogenesis and validity of the clinical syndromes. Stroke. 1991;22(11):1374-1378.

pubmed doi - Bamford JM, Warlow CP. Evolution and testing of the lacunar hypothesis. Stroke. 1988;19(9):1074-1082.

pubmed doi - Arboix A, Morcillo C, Garcia-Eroles L, Oliveres M, Massons J, Targa C. Different vascular risk factor profiles in ischemic stroke subtypes: a study from the "Sagrat Cor Hospital of Barcelona Stroke Registry". Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102(4):264-270.

pubmed doi - Arboix A, Tarruella M, Garcia-Eroles L, Oliveres M, Miquel C, Balcells M, Targa C. Ischemic stroke in patients with intermittent claudication: a clinical study of 142cases. Vasc Med. 2004;9(1):13-17.

pubmed doi - Arboix A. Alvarez-Sabín J, Soler L for the Cerebrovascular Study Group of the Spanish Society of Neurology. Nomenclatura de las enfermedades vasculares cerebrales. Neurologia 1998; 13 (Suppl 1): 1-10.

- Special Report from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke: Classification of cerebrovascular diseases III. Stroke 1997; 28: 1590−1594.

- Arboix A, Lopez-Grau M, Casasnovas C, Garcia-Eroles L, Massons J, Balcells M. Clinical study of 39 patients with atypical lacunar syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(3):381-384.

pubmed doi - Gan R, Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Roberts JK, Boden-Albala B, Gu Q. Testing the validity of the lacunar hypothesis: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study experience. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1204-1211.

pubmed - Arboix A, Garcia-Eroles L, Massons J, Oliveres M, Targa C. Hemorrhagic lacunar stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2000;10(3):229-234.

pubmed doi - Kase CS, Mohr JP, Caplan LR. Intracerebral hemorrhage. In: Mohr JP, Choi DW, Grotta JC, Weir B, Wolf PhA, eds. Stroke. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2004: 327-376.

- Mori E, Tabuchi M, Yamadori A. Lacunar syndrome due to intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1985;16(3):454-459.

pubmed doi - Blecic SA, Bogousslavsky J, van Melle G, Regli F. Isolated SMS: a reevaluation of clinical, topographic, and etiological patterns. Cerebrovasc Dis 1993; 3: 357−363.

- Lodder J, Boiten J, Heuts-Van Raak L. Sensorimotor syndrome relates to lacunar rather than to non-lacunar cerebral infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(11):1097.

pubmed doi - Arboix A, Martinez-Rebollar M, Oliveres M, Garcia-Eroles L, Massons J, Targa C. Acute isolated capsular stroke. A clinical study of 148 cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107(2):88-94.

pubmed doi - Benavente O, White CL, Roldan AM. Small vessel strokes. Curr Cardiol Rep.2005;7(1):23-28.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Neurology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.